Letter to the American Church

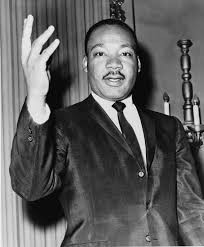

Eric Metaxas’s Letter to the American Church is the first book I’ve read by this author, but his biography of Bonhoeffer is familiar to me, along with his reputation as a thorough researcher with the skill to share his extensive knowledge in a readable, accessible form. Letter to the American Church draws strength from both Metaxas’s knowledge and skill as he exhorts Christians to avoid the mistakes of the German church leading up to World War II. Tracing the similarities between our time and 1930s Germany, and offering Dietrich Bonhoeffer as an example of a prescient, consequential Christian in a time when the church at large failed to act, the book makes a cogent case for bucking the evangelical trend of keeping a low profile on political matters for fear of either giving offense or inviting consequences by speaking out against harmful narratives favored by an increasingly oppressive state.

Our current president speaks frequently of “the soul of the nation,” echoing a campaign slogan that frames him as a sort of high priest of democracy. This is an unapologetically religious mantle that implies the administration’s political views carry nothing short of divine authority. I’ve been increasingly disturbed by this over the last two years as political initiatives like abortion on demand, gender fluidity and transition for minors, gay pride month, drag shows in the military, and public school embrace of extremely detailed sexual instruction and pleasure reading for young children have been strongly advocated at the federal level. The moral and spiritual nature of these initiatives, the use of edicts and tax dollars to enforce many of them, and the refusal to honor the freedom of speech or conscience for those who dispute them raise plenty of alarms.

But what, I’ve wondered, can I — or should I — do? What is the role of the church? Not to tell everyone else they must follow the moral code of Christians. This is a free country, and adults of all stripes have long been free to practice their sexuality, inculcate their values in their children, and to seek abortion within limits. But these preferences cannot be inflicted on everyone else without denying them their equally protected freedoms. Yet this is happening today.

In Letter to the American Church, Metaxas describes Bonhoeffer’s 3-part approach to how the church should respond to political abuses in “The Church and the Jewish Question” (1933):

- In its role as conscience of the state, the church must clearly call out injustices and wrongs

- It should care for the victims of the state

- It should, if the state persists in its course, actively protest

I can think of examples here and there of the second and third actions. Crisis pregnancy clinics and care centers such as Care-Net that serve as an alternative to Planned Parenthood and other abortion providers offer a safe space for women with unwanted pregnancies. They provide counseling, information about options, and material support for women and unborn children. These kinds of clinics are frequently attacked and vandalized, and some in congress — Senator Warren has been quite vocal — defame them as fraudulent and are actively working to make them illegal. But these centers provide needed care for victims of a state bent on elevating abortion as the only alternative despite its damage to women and unborn children.

As for Christians actively protesting, examples include peaceful protests at abortion clinics, as well as those in libraries and at public schools to push back against inappropriate, emotionally destructive or politicized curricula that harm children and trespass on parental freedom.

But generally speaking, when it comes to Bonhoeffer’s first point, I’ve heard almost no teaching in church about where the church stands on these issues, or who the victims of injustice are. Is this because evangelical pastors think everyone already knows? Or because they don’t want to alienate parishioners? I remember being turned off by a church I attended in grad school because the sermons were often heavily political — to the point of offering the pulpit to a chosen candidate for office. But that’s different from the “calling out” Bonhoeffer speaks of here: a clear confirmation of how a given initiative is contrary to the truth, who is suffering as a result, and how we can respond.

Without “being political,” some churches are good at being responsive to practical needs in the community, and at banding together with other churches to provide things like food and clothing and shelter to those in need. It’s important to “feed the body before you try to feed the soul.” But what if the hungry bodies are caused by a callous government that enriches itself, and its preferred political issues, at the expense of security, a healthy economy, and those not identified with a favored group? At some point, identifying and solving political problems can go a long way toward feeding the hungry. For example, my church is in a town with a growing homeless problem. If in addition to providing care, churches speak out on how this problem grows from policies, this could conceivably achieve the same result: feeding the hungry. But it could also help bring about a solution to the problem — something the homeless themselves are not able to do.

This book is the third I’ve read that considers the church’s role on culture these days. The first two were by Rod Dreher: The Benedict Option, which examines the idea of the church coming together and modeling strong community rather than asserting itself through political statements in the public square; and Live Not By Lies, which examines the resemblances between the “soft totalitarianism” spreading in America and the hard totalitarianism of formerly communist countries, with an eye to how Christians can be alert to the signs and resistant. Much of the book focused on how dissidents formed underground communities to keep the faith alive and support one another.

These books focused on how to preserve and strengthen authentic Christian community. I agree that this is important, and that Christian practice must be consistent with its talk in order to have integrity when modeling our faith. But The Benedict Option in particular seems to overlook Bonhoeffer’s idea of the church as the conscience of the state. I understand that some manifestations of evangelicalism in politics have come across at times as more sanctimonious than authoritatively truthful. But unfortunately, the state is actively on the offensive on various political fronts, and these are the venues where it must be met.

What should this look like? Metaxas’s book is important food for thought. (One result of this is that this post consists much more of the thinking it stimulated than its content!) There is a study guide available, and the book would be a profitable read for a group to study together. I recommend Letter to the American Church for any Christian who looks at the current state of the country and asks, what is my role?