The First Men in the Moon

I read H.G. Wells’s First Men in the Moon while creating a course on C.S. Lewis’s Out of the Silent Planet, the first book in Lewis’s Ransom trilogy. Lewis was a fan of sci-fi, and he acknowledges his enjoyment of Wells’s novels and alludes to this one several times in the pages of his own first foray into the genre.

First Men in the Moon isn’t a book I’d have picked up without my interest in Lewis, but I found it absorbing nonetheless. It tells of a scientist (Cavor) who teams up with a more entrepreneurial playwright (Bedford) to attempt a moon voyage using his invented anti-gravity material “Cavorite.” The two succeed, and on arrival they discover a civilization of highly intelligent insect-like creatures called Selenites that live not on, but inside, the moon. Long story short, Bedford makes it back to earth, but Cavor remains on the moon and transmits a number of messages back to earth about his observations among the Selenites. The transmissions end after Cavor tells the Selenites about human history and war. The Selenites apparently don’t want any more visitors to learn how to make Cavorite and come to the moon.

At many points I was reminded of Out of the Silent Planet while reading Wells. For starters, Weston and Devine, the physicist and entrepreneur who kidnap Ransom and take him to Mars in Out of the Silent Planet, share some similarities with Cavor and Bedford. Overcoming language barriers with intelligent beings in space, discovering non-human rational species in highly organized societies, and being questioned by intelligentsia and, eventually, the ruling power of the extraterrestrials, figure prominently in both books. But these and other similarities are overshadowed by the contrasts. Lewis’s conception of the cosmos is colored by his Christian faith and given a distinctly Medieval flavor; rather than cold, vast, empty space, we find “the heavens,” ablaze with light and beauty. The societies Lewis’s hero encounters in his travels are utopias, whereas Wells’s book presents something darker, though we’re left wondering how fully his protagonist realizes it.

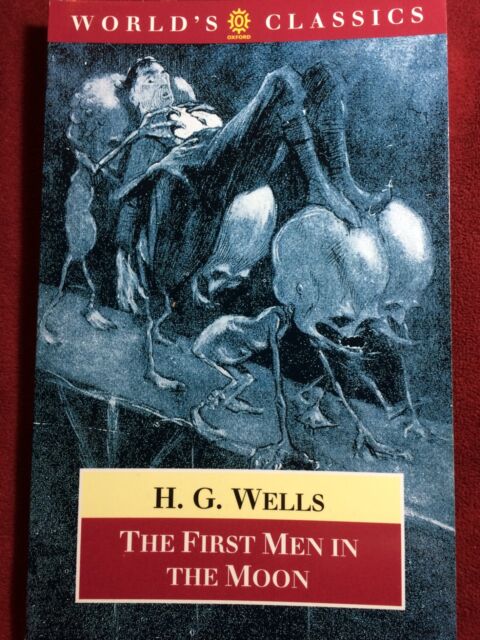

Cavor’s missives from the moon provide us with a lot of information about the Selenites, who not only resemble something like giant ants, but act like them in their unceasing industry and high level of social organization. Cavor admires many aspects of their society, starting with the way they assign everyone a vocation at birth. There are shepherds and butchers (large beasts called “Mooncalves” serve as a staple of their diet); fishermen; intelligentsia with large, transparent brains; mathematicians and linguists and others in charge of storing and remembering. It’s a society without freedom, and in this sense it has much in common with the world the N.I.C.E. wants to create in Lewis’s third novel in the series, That Hideous Strength. It’s impossible not to think of “the Head,” the product of a grotesque experiment in Hideous Strength that purportedly directs the activities of the N.I.C.E. A portion of its skull has been removed to stimulate hypertrophic brain development. In Wells’s story, Cavor eventually appears before the Grand Lunar, ruler of the Selenites, whose brain is so large it dwarfs everything else but his eyes and must be repeatedly bathed by cooling spray dispensed by his lackeys. Like the N.I.C.E. scientist in Lewis’s novel, Cavor admires this overgrown brain because he thinks it equates to more intelligence. At one point he remarks that the Selenites are not limited by a skull that prevents their brains from growing indefinitely.

Cavor is disturbed by some of the Selenite measures used to train up young to a vocation, but he tries to talk himself out of his revulsion by suggesting it’s better to do this than to wait till they’re adults and unleash them on society without a vocation. He is also bothered when he comes across a group of agricultural Selenites and finds several flat on their faces and motionless. His guide tells him they’re not dead, merely sleeping because they lack work at the moment. Their deathlike appearance and lack of any mental occupation outside of their assigned work trouble Cavor, and though he defends the Selenite practice, he avoids the place afterward. In their different ways, both Wells and Lewis raise questions about the totalitarian regimes that seem the inevitable consequence of scientifically perfected efficiency without humane, moral underpinnings — what Jacques Ellul calls “technique” in The Technological Society.

Though I read Wells mainly to see how it might relate to That Hideous Strength, I actually thought of aspects of other books as well: Perelandra, in which Ransom passes through deep subterranean caves on the planet Venus, seeing strange and sometimes insectoid creatures; Golg, the earthman in The Silver Chair who longs to leave Underland and return to the land of Bism deep beneath Narnia; The Abolition of Man and That Hideous Strength, with their critique of the systematic way educational institutions seek to create “objectivity” by numbing natural repugnances to things that run contrary to the “Tao,” or universal moral law.

Reading First Men in the Moon alongside Lewis’s book was a fascinating reminder of how what we read furnishes our imaginations with analogies and images that can take on a life of their own. In the same way we can sometimes look at a child and see both parents in the child’s features or movements, we can sometimes see in a story traces of books that have made an impression on the author. It can add richness to the reading to see how those traces are recombined and redeployed in the service of another artist. But I’m glad it’s not a requirement for literary study to read all the books that were meaningful to an author we like. I did my best to enjoy The First Men in the Moon, but in the end it was too dark, too cold, too claustrophobic, and too full of giant insects.