The Bronze Ring

This morning, before anyone else was up, my Kindle Fire went berserk. I was checking news headlines when suddenly an audio clip began playing. I tried to turn down the volume, then turn off the device. After a full 30 seconds, it went dark.

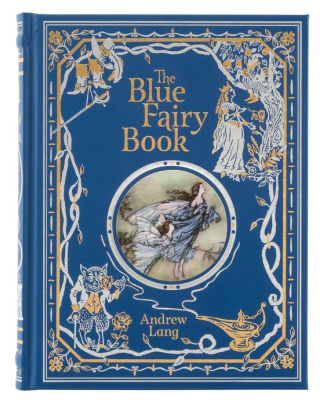

On restarting it, I immediately went into my Kindle library and started the self-reading function in the first book listed so I could turn down the volume and head off any further loud disruptions to the rest of my family’s sleep. The story was “The Bronze Ring,” which I haven’t read in ages, and it intrigued me immediately — enough that I read to the end instead of turning back to other reading.

It’s been a long time since I read a fairy tale, and I was struck by its… strangeness. For one thing, its tone is completely matter-of-fact while reporting one outlandish event after another: a magic ring, an island populated by talking mice, a conjured boat with golden hull, silver mast, and brocade sails. For another, episodes of extraordinary cruelty are reported with utter indifference: for example, the gardener’s son, hero of the tale, is instructed by a fairy to go to outside the village and incinerate the three dogs of different colors he finds there, then bag them up separately. After that, he’s to go to the palace and boil the king to restore his youth. All goes as planned, and we’re informed that “very soon the king was boiling away.”

I’ve been told that a common purpose of fairy tales was to inculcate moral principles, but morality seemed irrelevant at best in this fictional universe. It requires an acknowledgement of pain, or of human limitation, or virtue, doesn’t it? In this tale, the Good Guy wins. He’s kind to the old woman who turns out to be a fairy, and perhaps he is rewarded accordingly with the happy ending. He is also clever. But the events of the story are hard to conceive of as moral lessons.

Speaking of the events of the story, the other thing I was struck by is how meanderingly it developed. I suppose it’s technically a picaresque, a tale where the plot is advanced through spatial movement rather than through character development. Interestingly, the story begins with the problem of humans alienated from nature, because no one can make anything grow in the king’s large garden until they seek out an actual gardener, whose son becomes the good guy of the tale. In that sense the fictional situation could serve as an allegory of what our destructive agricultural policies and practices have done to our food supply through soil depletion and erosion, pesticides, fertilizers, and so on. But of course it isn’t a story about farming, even though it touches on the idea of stewardship among other things.

Which is… like life. We deal with various matters “among other things.” We live out a number of stories at once, all the time, each with its own antagonists and problems to be solved, and each resolving at a different pace. The winning of the princess, the successful completion of the first trip the gardener’s son takes (in which he earns the bronze ring), and the successful completion of the second trip (in which he accidentally leaves behind the magic ring to be stolen by an evil sorcerer), the difficulties of the island of talking mice that he threatens into helping him — all these stories get resolved at different times and in different ways.

I guess my point here is that I’ve grown accustomed to fiction that offers a more intentionally shaped and ordered artistic version of life. That’s what I expect from a work of art: something coherent, the structure of which I recognize and follow intuitively. But aside from the outlandishness of its fictional materials, this fairy tale felt more like life: confusing, requiring you to keep moving forward through a sequence of strange events, hoping for the best. I felt impatient at times, but I kept going to see how on earth it would end.

Now that I’ve gotten this far, I can tentatively see the outlines of a moral universe in the story. Bad people are dishonest and spurn kindness. Good People are not exactly compassionate — the gardener’s son is kind to the old fairy, but he (and the narrator) are indifferent as he carries out his assignments with the dogs and the sultan — yet they follow instructions. There is a path to follow out of adverse moments, and when someone shows up and tells you what to do, you do it. And finally, Good People know how to take advantage of vulnerability to get others to do what they need. The gardener’s son does this with both the minister’s son (who submits to being branded, resulting in his exposure, later, as a fraud) and the mice (who despite setbacks recover the ring).

All of which goes to show that a fairy tale can get under one’s skin with its combination of cold, shrewd insight and alternative reality. This one operated very much like a dream, leaving me with stand-out moments and pictures that shock and bemuse. I’m not totally sure what the draw was, but it was oddly refreshing to read, especially as a contrast to the news stories I was initially reading. In a time of wearisome oversimplification, polarization and “we now knowism,” this story beckoned from a world where mystery is allowed, where people and events are complicated, and where, quite literally, anything can happen.

2 Comments

Ruth

I always get so happy when I see you’ve put something up. This is such a great post! I used to love those Andrew Lang fairy tale books when I was a kid, but I haven’t read any in many many years.

Jeane

I read those fairy tale collections as a kid, too. I wonder how I’d find them again now, as an adult. Probably the different style of pacing and details, and the odd morality, would make it the kind of book I have to be in “the right mood for” now. I vaguely remember this particular story, too.