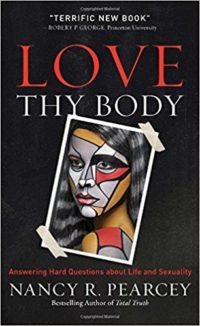

Love Thy Body

There aren’t many books that I feel like buying and giving to everyone I know, but this one fits into that category. Written by Nancy Pearcey, author of Total Truth, Love Thy Body offers a clear analysis of the various body issues our culture is facing morally, legally and politically: abortion, euthanasia, homosexuality, transgenderism, the hook-up culture, marriage. Examining these issues from the perspective of a Christian faith and worldview, she is able to discuss the underlying issues with a lucidity, breadth of research, and charity that are unmatched by anyone writing today.

There aren’t many books that I feel like buying and giving to everyone I know, but this one fits into that category. Written by Nancy Pearcey, author of Total Truth, Love Thy Body offers a clear analysis of the various body issues our culture is facing morally, legally and politically: abortion, euthanasia, homosexuality, transgenderism, the hook-up culture, marriage. Examining these issues from the perspective of a Christian faith and worldview, she is able to discuss the underlying issues with a lucidity, breadth of research, and charity that are unmatched by anyone writing today.

The main idea of the book is that our thinking on these issues is pervaded by a dichotomy between body and mind. This is the fruit borne of a long gestation from at least the Enlightenment, when DesCartes made his famous statement “I think, therefore I am.” In that basic idea is the DNA of postmodern dualism that privileges the mind over the body — a view that runs counter to the biblical endorsement of the body (and all God’s creation) as a gift from God, intrinsically valuable. Our bodies are inescapably part of our identities, the outward expression of our being. For the Christian, a human being is a whole person, body and soul intermingled.

But the devaluation of the body is nothing new. Pearcey points to the Gnostics, who were among the first to challenge the notion that God could be embodied in the Incarnation, as an early example. Today we have a similar snobbery at work in every one of the issues she explores here. For instance, take abortion. “Virtually all professional bioethicists agree that life begins at conception,” Pearcey writes. Why then is there not agreement that abortion is immoral? Because mere physical life, according to personhood theory, is not enough to make a fully human being with rights and moral status. Moral standing is conferred by a certain level of cognitive function and consciousness; biological life is not enough. Till then, even a living human is considered a mere blob of tissue that can be experimented on, destroyed, or sold for its parts.

I have never thought of the issue in just this way, but it is not a big jump to other issues as well. The “right to die” movement places a similar value on cognitive function over bodily life. Same sex marriage advocates and transgender individuals disregard biology as relevant to identity. And the dismal separation between sex and love in the hook-up culture testifies to the same split. In every case, a dichotomy between body and mind is assumed, and the mind wins out. The irony is obvious: despite an avowed allegiance to materialistic science as the final authority, this line of reasoning depends on unverifiable and unscientific concepts. Who decides when a living human becomes a person? How does one conceive of a self without a body, here in time and space?

Though it might seem that materialists value our physical being because they assume that’s all that exists, it is Christianity that takes a high view of the body, seeing a human life as inherently valuable regardless of whether the mind meets some external standard of “fitness.” We are valuable because God made us, and we respect others for the same reason. Pearcey devotes a chapter to unpacking the thought foundations in each issue, explaining the contrast between the dominant postmodern mentality and the Christian view, based on Scripture. She also suggests some wonderfully practical, compassionate, and comprehensive ways Christians can respond.

One of her suggestions is to eliminate “offended” from the Christian vocabulary in talking about these things. I appreciated this. For Christians, developing a more complete understanding of what our own faith teaches is a much better place to start. We have life to offer in a culture of devaluation and death.

I loved the clarity and thoroughness with which Pearcey worked through these matters, bringing new insight and deep knowledge. As she notes, most people would propose that we all believe what we want as long as it doesn’t step on anyone else’s toes. But someone’s worldview is always what ultimately shapes public policy, education, and justice. As I was reading this book, I had several opportunities to see its relevance in the headlines. There was this story about an “advanced directive” in New York that advocates halting food and water in cases of advanced dementia. (How many of us have someone near and dear who suffers from dementia or Alzheimer’s?) Then there was this one that announces the book Our Bodies, Ourselves will stop publishing. (The notion that our bodies have anything to do with who we are is out of step with the postmodern ethos.) Of course any news about AI or the advance of technology, such as this one, regards artificial “thinking” to be far superior to those encumbered with bodies. (Doesn’t the fact that a human brain functions within a body grant it superior insight on moral issues? Does a machine that merely compiles data actually achieve wisdom? What is the difference between knowledge and data? Are memory and emotion liabilities to speculative reasoning — or advantages? I could go on with these questions all day. . .)

Worldview matters. The dualism that underlies so much of the public, “pomo” mindset inevitably cheapens life, reduces personal freedom, and turns power over to the state. In the early church, Pearcey points out, the high view of the body was as countercultural as it is today. In ancient Rome, it was routine to enslave children and women, and marriage was regarded as a mere legal, financial entity that coexisted alongside every kind of promiscuity and abuse. In contrast, the Christian respect for all human life (including women and children), and the view of marriage as a relationship within which both love and sexual satisfaction belonged, attracted many converts. Christianity was easily recognized by its fruits in quality of life, joy, and meaningful community. These are the natural results of a biblical worldview lived out in each of the areas Pearcey examines in this book. Love Thy Body stands out as an indispensable resource for anyone desiring a deeper understanding of our culture’s confused, joyless ethics of the body.

2 Comments

bekahcubed

How fascinating! I don’t know that I’d have ever thought of linking all those various social issues together (except maybe to contrast “socially liberal” vs “socially conservative” positions), much less relate them to Gnosticism vs. a Christian view of the body, but it makes sense. I’m going to have to get myself this book!

hopeinbrazil

Excellent review. I’ll certainly be on the lookout for this book!