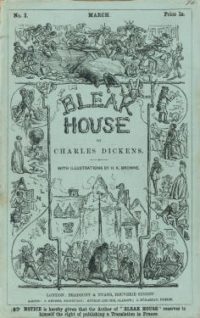

Bleak House

We are in the midst of a Victorian novel fest around here. Both daughters have been listening to Jane Austen (just a little earlier than the Victorians, but close enough) — Emma and Pride and Prejudice, courtesy of Librivox — and I have been rereading Dickens’ Bleak House, said by many critics to be his finest novel, and one I enjoyed very much the first time. (Great Expectations and David Copperfield are also among my favorites!) The noteworthy points of this tome are many and varied, so I thought I’d mention just a few of them here. The notion of “reviewing” this well established and substantial book seems preposterous, but noting a few features that stood out to me on this reading will be worthwhile for me to look back on if I revisit it again.

We are in the midst of a Victorian novel fest around here. Both daughters have been listening to Jane Austen (just a little earlier than the Victorians, but close enough) — Emma and Pride and Prejudice, courtesy of Librivox — and I have been rereading Dickens’ Bleak House, said by many critics to be his finest novel, and one I enjoyed very much the first time. (Great Expectations and David Copperfield are also among my favorites!) The noteworthy points of this tome are many and varied, so I thought I’d mention just a few of them here. The notion of “reviewing” this well established and substantial book seems preposterous, but noting a few features that stood out to me on this reading will be worthwhile for me to look back on if I revisit it again.

- The narrative switches back and forth from an omniscient narrator to “Esther’s narrative” — a telling from within the sensibility of the heroine, Esther Summerson. We get the intimacy of a first-person narrative in the Esther chapters, and the breadth of perspective the omniscient narrator gives us in the other chapters. The two perspectives work well together; we feel a sense of personal investment, but without the limitations of Esther’s scope of knowledge.

- Esther herself can be somewhat cloying. She is Dickens’ “angel in the house,” the perfect representation of domestic virtue. Despite her mysterious history and lack of pedigree, she is extremely genteel and fits in well with her middle class guardian, John Jarndyce, and his other two wards, Ada and Richard Carstone. She always thinks of others before herself; she is self-effacing and humble; she scolds herself whenever she has a desire that runs counter to what she regards as conventional; and she is above all busy about Jarndyce’s estate, Bleak House. She makes the home a clean, charming, efficiently run, comfortable place, and though we never learn anything at all specific about how she manages this, we are told many times that she jingles her keys busily. She is likable, and we want her to do well. But occasionally I wanted to have a pointed chat with her about the virtues of plain honesty. She is dutiful to a fault, but somewhat disingenuous in her representation of this as what she legitimately desires at all times. But her compassion for others is the real thing, and we feel sorrow for her when she ends up disfigured by smallpox (though the disease is never named) as a result of caring for a poor, sick orphan named Jo.

- The benevolent Mr. Jarndyce is party to a suit in chancery that has lasted for many years without resolution. He has deliberately stopped following the case and made a life for himself that’s indifferent to what the outcome may be, but Richard, his ward, is not so lucky. He, and several others, are tragically depicted as characters who have been drawn into obsession over legal proceedings in the case Jarndyce & Jarndyce, and Dickens’ satire on the judicial system in England is scathing indeed.

- The cast of characters is incredibly extensive, and true to form, they are all revealed to be somehow connected in the end. Dickens’ sympathy is far-reaching, and as a psychologist he can be, sometimes, frighteningly on target. Though some are stereotyped stock characters, others seem to attract amazing sympathy in Dickens’ imagination. Sir Leicester Dedlock, an almost comedic figure in his sense of self-importance and preoccupation with trivial matters, rises to truly heroic proportions in his love and forgiveness for Lady Dedlock when he learns that her true history has been kept secret from him for many years. Another example is Caddy Jellyby, whose mother is a caricature of Esther Summerson’s polar opposite in her neglect of her family in favor of a humanitarian project in “Borrioboola-Gha.” Caddy successfully removes herself from her mother’s dysfunctional household only to find herself married to a man whose father is equally self-involved. Nevertheless, she is able to create a home of her own that is a loving and safe place for her family, and she is able to overlook her father-in-law’s flaws.

- Delay. Dickens needed to use it in the novel’s original serial publication, stretching the story out from one issue to the next between March and September of 1852. He is expert at making his audience laugh, making them weep, and making them WAIT. You have to be ready to relax and enjoy the ride or it gets frustrating.

- Mr. Bucket, one of the first detectives in English fiction, is a striking character able to relate to everyone, a solver of mysteries, an observer of details, seemingly at home at every class level and in every environment from country estate to Chancery Lane to London slum. He is less cosmopolitan but more likable than the later, more well-known Sherlock Holmes.

I could go on and on, but this will suffice to mark the territory this time around. Though Dickens himself was a complex, not entirely consistent character, I enjoyed the experience of Bleak House every bit as much on this reading as before — its comedy, its tragedy, its domesticity and raw social satire, its hominess and homelessness, its exuberant descriptions and jokes, and above all its happy ending that draws together an impossibly large tangle of plot strands into a neat, satisfying bow.