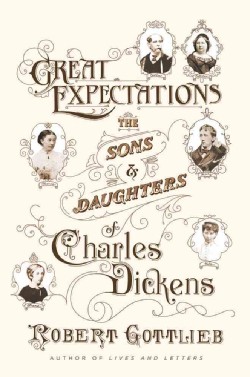

Great Expectations: The Sons and Daughters of Charles Dickens

Recently, I revisited with my daughters the book some have called Dickens’s masterpiece: Great Expectations. From its gripping opening scene between Pip and Magwitch in the bleak and isolated churchyard, to the concluding conversation with Estella on the grounds of Miss Havisham’s neglected estate, I marveled again at Dickens’s genius breathing life into his characters. Such a master at rendering loneliness and self-deception with merciless clarity, who cares so much for the poor and sounds the clarion call for reform, and who can weave such complex and intricate plots, must not be as self-deceived as the average person — right?

Recently, I revisited with my daughters the book some have called Dickens’s masterpiece: Great Expectations. From its gripping opening scene between Pip and Magwitch in the bleak and isolated churchyard, to the concluding conversation with Estella on the grounds of Miss Havisham’s neglected estate, I marveled again at Dickens’s genius breathing life into his characters. Such a master at rendering loneliness and self-deception with merciless clarity, who cares so much for the poor and sounds the clarion call for reform, and who can weave such complex and intricate plots, must not be as self-deceived as the average person — right?

Wrong. Robert Gottlieb’s readable and sympathetic Great Expectations: The Sons and Daughters of Charles Dickens reveals the most popular writer of the Victorian era as all too human. Each of Dickens’s ten children are introduced in the first half of the book, and we are given a glimpse of their family life and their relationship with their father as revealed through the novelist’s letters and other interesting sources. The second half describes how they fared after Dickens’s death.

The picture that emerges is complex. Dickens was certainly a dominating personality, by all accounts a man who loved his children very much and worked hard to set them on a course to success in later life. He was most enthusiastic about them when they were very young, but as they grew he was frequently critical and quite openly expressed his disappointment and pessimism about what he saw as his sons’ lack of focus and energy. Toward his two daughters he was less severe in his judgment. One daughter, Katie, and one son, Henry, achieved real distinction in later life and even won some approval before their father’s early death at 58. The others (with the exception of one, Dora, who died in infancy) were a mixed bag of decency and moderate success, and, in some cases, disgrace.

All of them regarded their father with something close to reverence and remembered their childhoods with fondness and pride. Their father was the starring personality, giving each child a nickname, playing with them in the garden and caring for them when they were sick, and creating and directing family dramatic productions. He cared for them very much and took his obligation to provide for and direct them very seriously. But his self-involvement often conferred a great sense of obligation on the children, too, and at times he seemed all too ready to be rid of them, sending several of them off to Australia in their teens.

Most of us have heard about Dickens’s early life — how his father’s debts landed the family in debtor’s prison, and how the young Dickens had to work in a blacking factory for a time. It’s perhaps less well known that after the tenth child was born, Dickens abruptly and brutally turned his wife out of the house and kept the children, complaining publicly of her laziness and poor mothering (of which there is no evidence), and frowning upon any interaction between the children and their mother. Her younger sister Georgina stayed on with him and took care of the children, and Dickens carried on an affair with the much younger actress Ellen Ternan. Gottlieb discusses the impact of this family split on the children, the youngest of whom was only six at the time.

About the only thing I was desperately curious about that Gottlieb didn’t discuss was Georgina Hogarth, the younger sister of Catherine Dickens who stayed on after her sister was ejected from the home. What a strange state of affairs! I learned much and appreciated the sympathy and candor of Gottlieb’s narrative, which left me with a picture of a brilliant, compassionate, self-involved, self-blind and at the same time deeply insightful artist whose public readership adored him almost as much as his family and friends. Charley, his oldest son, commented once that his father’s child characters were often more real to him than his children. Certainly this introduction to those who surely inspired and instructed him, whether he realized it or not, will deepen my future encounters with the fictional children of Dickens’s novels.

2 Comments

Amy @ Hope Is the Word

Interesting! I know nothing about Dickens and have so far only read GE (as a ninth grader), Two Cities, and Christmas Carol. I want to read more, of course.

How did the read-aloud go?

Janet

The girls loved it! With those long, complicated sentences and vocabulary, I stopped periodically when we were first getting started and asked, “You want to keep going?” Always the answer was an immediate yes. (Charlotte Mason knew what she was talking about!) It’s an amazing story with darkness and danger and obsession in it, but there’s also lots of humor and wit.

I think part of the initial draw was that Pip was such a young narrator at the start, and we meet him in the midst of a crisis. He’s easy to sympathize with and commands respect.