The Wild Trees

“I think I’ve found out the secret of making a dream come true.”

“What’s that?”

“Just don’t stop. Don’t stop. Don’t ever stop. If someone tells you something is impossible, do that thing first. Prove that it is possible, and keep going.”

So says Michael Taylor, speaking of his years-long quest for the tallest tree in the redwood forests. Richard Taylor’s The Wild Trees, as informative as it is about the ecology of the redwood canopy, is as much about the elite society of people who study and climb these trees as it is about the trees themselves. In these pages we get to know Michael Taylor, Steve Sillett and Marie Antoine in particular, but there is a whole supporting cast of characters who share their consuming interest in the life of old growth forests.

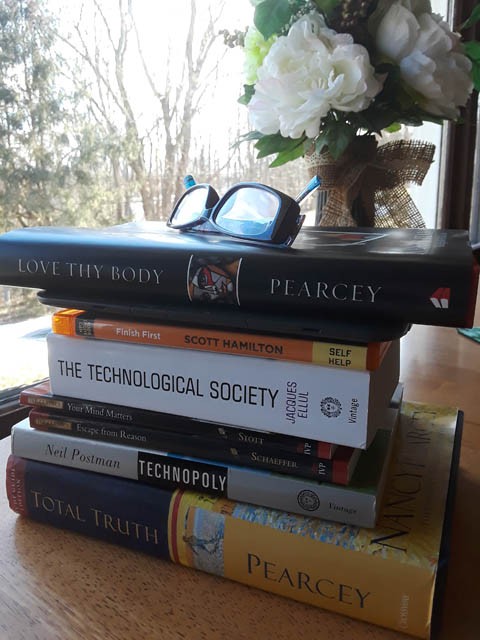

I learned about this book when I read Jason Chin’s Redwoods to my daughters. It was The Wild Trees that piqued Chin’s interest in the coast redwoods, and for me the process worked the other way around; it was Chin’s book that made me want to learn more about these trees that support an entire eco-system in their canopies. We can learn a lot from an organism that has been growing since the Parthenon was built, and, as Richard Preston makes clear, there is a spiritual impact as well from contemplating the longevity of a redwood. Most of the people in this book are living examples of people who find an anchor in the study of these trees. They are experts — some are high-level scientists conducting research, some are arborists, and some, like Michael Taylor, are self-taught. All are passionate enough about their interest to take risks, scaling trees as tall as 36-story skyscrapers and sometimes even sleeping in them.

The book is subtitled “A Story of Passion and Daring,” an apt description of these people. As I read about them, I found myself thinking a lot about the passionate nature, and how passion compels people to take risks and seek thrills and find empowerment even in settings that render their own smallness and powerlessness most dramatically. It’s an attractive quality, and most of the characters in this book exhibit it in more ways than just their attitude about trees. I find their put-it-all-on-the-line commitment of themselves to what they love very appealing.

I also noticed that what ultimately seems to draw them to the treetops, though, is the stability and endurance of these trees that have stood quietly in one place for thousands of years, enduring fire and storm and offering a hospitable habitat for any number of other organisms from lichens to salamanders to other redwoods growing from their upper branches. As long as they remain standing, several characters at different points explain, we’re going to be all right despite the trials and evils of the world. What underlies thrill-seeking seems to be anchor-seeking, and their passion for the forests results in qualities like faithfulness, protective care, and the kind of submission to external conditions essential to survival in high-risk situations like tree-climbing. The passion and energy of the people is ultimately balanced by more stabilizing traits, in the same way the vibrant life of giant trees ultimately is balanced by other organisms and forces in nature.

Of course I thought of certain fantasy stories involving trees. I thought of the sentient trees in Narnia, who come to the rescue at the end of Prince Caspian, and whose cutting in The Last Battle signals the end of the world. And I thought of the Ents of The Lord of the Rings. If ever a redwood were to take on consciousness and speech, surely it would be like Treebeard:

These deep eyes were now surveying them, slow and solemn, but very penetrating. They were brown, shot with green light. Often afterwards Pippin tried to describe his first impression of them.

‘One felt as if there were an enormous well behind them, filled up with ages of memory and long, slow, steady thinking; but their surface was sparkling with the present; like sun shimmering on the outer leaves of a vast tree, or on the ripples of a very deep lake. I don’t know, but it felt as if something that grew in the ground — asleep, you might say, or just feeling itself as something between root-tip and leaf-tip, between deep earth and sky had suddenly waked up, and was considering you with the same slow care that it had given to its own inside affairs for endless years.’

Although there were a few details I didn’t need as I worked my way through The Wild Trees, on the whole I found it to be an enthralling read, one that invited me to consider many things from the beauty and economy of nature to the mysteries of the human heart.

One Comment

Amy @ Hope Is the Word

This sounds interesting, Janet. Plus, this post makes me want to revisit Tolkien.