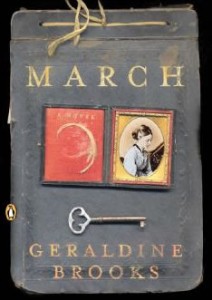

March

Last year, I was dazzled by Geraldine Brooks’ Year of Wonders: A Novel of the Plague. “How do people write books like this?” I wondered. “How can someone research such a seemingly unpromising subject so thoroughly — and then make it sing in a work of fiction?”

Last year, I was dazzled by Geraldine Brooks’ Year of Wonders: A Novel of the Plague. “How do people write books like this?” I wondered. “How can someone research such a seemingly unpromising subject so thoroughly — and then make it sing in a work of fiction?”

March is a book I had mixed feelings about at different points in the reading, but in the final analysis I found it quite thought-provoking and satisfying. Like Year of Wonders, March is well-researched as a historical work. Set during the Civil War, it offers a glimpse into the gritty reality of the Union army in both its principle and practice. But it takes as its subject the rather hallowed March family of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women — specifically, Mr. March, who is absent from the domestic scene for most of Alcott’s novel, “away down south where the fighting is.”

Brooks explains that since many of the other characters in Little Women are based on real people, she took Bronson Alcott, Louisa May’s father, as a model to expand imaginatively on Mr. March’s character. Alcott was a noted Concord Transcendentalist, a friend to Emerson and Thoreau as well as a vegetarian and primary vision-caster in the Utopian experiment “Fruitlands.” He was born on a Connecticut farm and traveled south as a peddler as a young man. Mr. March resembles him in this detail, as well as in his qualities as an intellectual, vegetarian, radical, and dreamer. But Alcott was not a minister, and it’s as a Unitarian chaplain and fervent Abolitionist that March enlists with the Union army.

Brooks explains in the afterword that when her mother recommended Little Women to her at age 10, she warned her that “Nobody in real life is such a goody-goody as that Marmee.” Indeed, one of the foundational principles of March seems to be the demythologizing of the Marches, particularly Marmee and Captain March. She is depicted as an angry woman, he as an outwardly proper but inwardly undisciplined man with all kinds of inconsistencies and blind spots as well as a talent for alienating people. Yet somehow, by the end, the pain and horror of war have forged a character that I cared about and admired in some ways. The novel offers a poignant insight into the Marches’ marriage, too, shifting the point of view between March and Marmee and revealing how the two have misunderstood each other at some crucial points, yet still they don’t give up.

What kept me reading, I think, is that the novel is a study of what happens to principle when it’s plunged into what one of the heroic black characters calls “the river of fire.” What happens to March’s grand ideals? What nugget lies at the core of marriage and survives disillusionment? What happens to the Abolitionist cause when fought for by a Union army that includes racists? Though I didn’t buy all the answers Brooks suggests through the action of the novel, I found the questions intriguing and worth asking.

It’s been years since I read Little Women, but of course I have to reread it now — and it’s a free download on the Kindle. Looks like I’ll be hanging out at the Marches’ Concord hearth for awhile!

9 Comments

Polly

Thanks for this review! I have just finished “The House of Brede” by Rumer Godden and “Naomi’s Daughters” by Walter Wangarin and am left casting around for what to read next. I have this book! And I am looking for something Civil War themed as we are heading to the Shenadoah Valley and Appomatox Court House next week for a mini vacation.

Amy @ Hope Is the Word

I think I’d like to read the first one by Brooks that you mention–Year of Plague–but I’m not sure I want my Marches demythologized. ;-) It does sound intriguing, though.

Barbara H.

I don’t think I could take the demythologizing of some of my favorite literary characters! I do remember hearing/reading somewhere that Mr. Alcott had some extreme beliefs, wanting at one point to go join the Shakers except but didn’t because it would have grieved his family.

Janet

Yes, I have mixed feelings about books that tinker with well-loved literary characters too.

Polly, this might be perfect reading for your trip!

bekahcubed

I really enjoyed Brooks’s People of the Book when I read it a couple of years back. Having just read Little Women (and very much enjoyed the “mythology” of the Marches), I’m not sure I’d really like to demythologize the Marches either.

Nevertheless, at some point or another, I imagine I’ll be reading this book (since I’m pretty sure it’s at my library!)

Susan (Reading World)

I read this awhile back and also had mixed feelings. Good writing and a compelling story and all…I just couldn’t make the characters mesh with the Little Women story as I remembered it.

Janet

I agree. I ended up reading it as more of a stand-alone story.

Alice@Supratentorial

I enjoyed March but Little Women has never been one of my favorite books so there wasn’t the same “don’t mess with my friends” feeling that I think some people have. I have enjoyed all of Brooks’ books that I have read (A Year of Wonders, People of the Book and March). I do think that she tends to impose too much of modern issues and sensibilities on her characters which sometimes read as more of a lecture than as true to the character to me. But she’s such a good writer and overall the books are so wonderful that I forgive her each time.

Janet

Well said! — I’ve felt the same way, and I too have forgiven her both times I’ve read her books.

I picked up Little Women to reread it after finishing March, but I confess that I found the first chapter so saccharine I haven’t picked it back up.