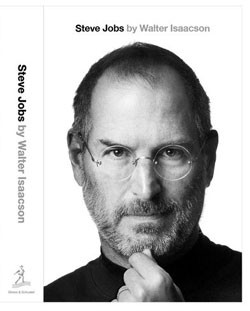

Steve Jobs

Though I’m neither an especially tech savvy person nor an Apple devotee, lately I’ve been hearing about Steve Jobs everywhere. He seems to be the one people like to quote, especially his comments about designing not the products people want, but the ones people would want if they knew they existed. When my husband watched a documentary about Jobs a few weeks ago and told me about it, that settled it. I had to read this bio by Walter Isaacson.

Though I’m neither an especially tech savvy person nor an Apple devotee, lately I’ve been hearing about Steve Jobs everywhere. He seems to be the one people like to quote, especially his comments about designing not the products people want, but the ones people would want if they knew they existed. When my husband watched a documentary about Jobs a few weeks ago and told me about it, that settled it. I had to read this bio by Walter Isaacson.

The book offers a readable portrayal of a very complicated personality. Jobs is in some ways the quintessential American hero. He’s an orphan, not a child of royalty. His adoptive family was middle class, not a place of privilege. He dropped out of college. He made it big using his brains and ingenuity, without any help from an Ivy League transcript or a famous benefactor. Though he died of cancer a few years ago, the company he co-founded (with Steve Wozniak) is still tremendously successful. When it comes to fitting the pattern of the self-made man, Jobs pretty much nails it.

But there is a dark side to this mythology, too. Jobs was equally famous for his brutal honesty and explosive temper. Even those closest to him wondered at times if he simply lacked the filters that bear witness to shared humanity, but his use of meanness was so strategic that it seems to have been intentional. He was legendary for his intensity and drive for excellence, and he forged a company the goal of which was to create great products. His success at building an “A Team” despite his often boorish behavior testifies to what many have called his “reality distortion field” — his insistence on what seemed an impossible standard of performance that, through the sheer force of his personality, he enabled others to believe in and achieve.

I admired Jobs’s simple, elegant design aesthetic, but he came across as the ultimate control freak with his belief in end-to-end design — creating every element of a product from the design of a device to its operating system and software to its user interface. Though he started out as a hacker himself, he scorned “open system” philosophy that promoted licensing products to multiple users. Though being able to “mix and match” elements of a product encourages competition and gives consumers more choices, the idea of contaminating any Apple product with “outside” elements was heresy to Jobs. He viewed the world in binary terms; people were either villains or heroes (his terms are more profane than I want to quote here), and products were either amazing or total garbage. It’s hard not to hear a contempt for consumers: “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them,” he declares. He was so protective of his creations that eventually even the screws were hidden and the batteries were inaccessible in his devices. No one could even look inside and see how they worked.

I found myself disturbed and angry at how much this controlling tendency translated into megalomania. It’s sobering to consider how much our lives are affected by people we don’t know at all, whose beliefs and values don’t represent us. Jobs transformed six industries: personal computers, animated movies, music, phones, tablet computing, and digital publishing. This affects how countless Americans experience their lives every day. But more troubling is the glimpse we get of his influence into politics, news, and education. Isaacson provides us with an extended experience of the world of an industry giant operating in a sphere most of us don’t get to see.

I was struck again by how the power base in our country seems no longer to be elected political office, but big business. A college drop-out, Jobs was not well educated himself, and he was filled with intellectual eccentricities. What business does he have advising the president on what American education should look like? (Not surprisingly, Jobs’s view involved eliminating the human element as much as possible: “All books, learning materials, and assessments should be digital and interactive, tailored to each student and providing feedback in real time.”) What business does any single individual have advising Rupert Murdoch on what news venues should exist or not? (Jobs advised him to give Fox News the axe.) What business does a CEO with personal interests have offering to create the ads for the president in his 2012 campaign? (He grew annoyed and didn’t do it when the president’s chief of staff was not totally deferential.) We didn’t elect Steve Jobs — or for that matter, any of the other tech giants who met with Obama in February 2011 to strategize about what was best for the country.

That session appears to have had an effect. The suggestion the president liked best was Jobs’s idea of producing more “engineers”:

These factory engineers did not have to be PhD’s or geniuses; they simply needed to have basic engineering skills for manufacturing. Tech schools, community colleges, or trade schools could train them… If you educate these engineers, we could move more manufacturing plants here.

“Engineers”? Or worker bees? In any case, I read this against the backdrop of the president’s recent proposal of taxpayer subsidized community college for everyone, and it’s not hard to connect the dots.

We didn’t elect these business leaders to run the country — or did we? It strikes me that we vote more with our consumer choices than with our ballots. What we buy — and perhaps become dependent on — is more powerful than who we vote into office when it comes to shaping the future. We know crony capitalism exists, but in these pages we get a closer look, and I found it deeply offensive.

“Like many great men whose gifts are extraordinary, he’s not extraordinary in every realm,” Jobs’s wife explains. “He doesn’t have social graces, such as putting himself in other people’s shoes, but he cares deeply about empowering humankind, the advancement of humankind, and putting the right tools in their hands.” One admires the evangelistic zeal of a person who seems not to be in it for the money. But ego isn’t much better as a motivation, and it makes me uneasy to think about what “advancement of humankind” means to a man who seemed unable to recognize the fundamental value of individual human beings or the richness of a diverse, free world.

The sad thing is that Jobs originally saw himself as a revolutionary. This 1984 ad for the Macintosh depicts his company as the sole independent spirit in a world dominated by influential, established businesses that turn out mediocre products. His company was the hope of the world, the only one empowering the average person to own an elegant and effective pc. But by the end, one wonders if the face on the screen is a better fit.