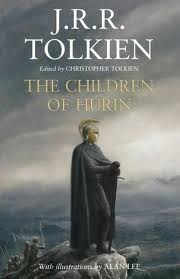

The Children of Hurin

A deadly peril has come upon us, which only great hardihood shall turn aside. But in this matter numbers will avail little; we must use cunning, and hope for good fortune… For I do not believe this Dragon is unconquerable, though he grows greater in strength and malice with the years. I know somewhat of him. His power is rather in the evil spirit that dwells within him than in the might of his body, great though that be…

So says Turin, son of Hurin. A dragon — no, a Dragon — needs slaying. A great-uncle of Elrond must avenge his father’s injustice at the hands of a predecessor of Sauron who spreads his dark thought over Middle Earth. A family is cursed, shattered, seeking restoration. Turin emerges in this posthumous Tolkien tale to face the evil dragon Glaurung, who is subservient to Morgoth as the one ring will be subservient to Sauron 6,000 years after the action of this story.

That’s Turin, reflected in the eye of Glaurung in Alan Lee’s illustration above. Indeed the gaze of this diabolical entity serves as a mirror for Turin. The excerpt above gives a taste of both this tale’s spiritual suggestiveness and its darkness. It was interesting for me to read this after Waking the Dead, with its references to spiritual warfare. But even without that precursor to my reading experience, it would be hard to miss the cosmic scope of the good vs. evil struggle in The Children of Hurin. Glaurung is an accuser and a deceiver as well as a destroyer.

But I’ve gotten ahead of myself. The Children of Hurin is a tale from the background mythology of Middle Earth, assembled by Christopher Tolkien, but from manuscripts written by J.R.R. Tolkien and only minimally edited. I found this article by Brian Appleyard offered a fascinating perspective on this work in the context of Tolkien’s other writings. It rightly notes that the timing of its publication (2007) brought the focus from the films back to the books, in which “The modern mind is clearly being dragged by the scruff of its neck away from its literary comfort zone.”

Recently, a couple of people have mentioned that they struggled in trying to read Tolkien. I struggled myself when The Hobbit was assigned in 7th grade; I remember the teacher slapping my graded exam on my desk and muttering, “It’s a good thing you can write, Janet!” Meaning, I suppose, that it was obvious I hadn’t read the book but had entertained her with my flowery writing. (?) It wasn’t till 20 years later that the book drew me in like a lit fuse that burned right on through LOTR.

The Silmarillion, though, is a different story. Tolkien considered it his masterpiece. I’ve tried two or three times, and haven’t been able to read it with its more elevated diction and — oracular? — mode.

The Children of Hurin falls between Lord of the Rings and Silmarillion in its style. The narrative voice is much easier to contend with than The Silmarillion. But the characterization is more flat than LOTR. It reads more like a myth whose characters are static, and move through a series of adventures — it’s a picaresque, I suppose — that carries them to their ultimate fate without changing them.

There were times I wanted to scream at Turin. He’s so predictable, in tragic ways. He seems to go from one bad decision to another. (Can you tell I’m parenting book at the moment?) But… I hate to point out that this is sometimes all of us. Often I’m less of a bildungsroman character in real life, less of a changing and growing person, and more a person who behaves as if she’s already set in stone. Turin may not be an example of flat characterization, but of human nature, in this respect — especially when he’s hampered so often by faulty information and deception. (…again, as we are.)

I have to mention Alan Lee’s illustrations. Alan Lee did the concept art for the movies, and he’s illustrated a number of other books including Black Ships Before Troy. He has captured the mood masterfully in The Children of Hurin, and the illustrations invite you to stop and ponder. They add a whole dimension to the work.

I have to mention Alan Lee’s illustrations. Alan Lee did the concept art for the movies, and he’s illustrated a number of other books including Black Ships Before Troy. He has captured the mood masterfully in The Children of Hurin, and the illustrations invite you to stop and ponder. They add a whole dimension to the work.

This reading experience was different than LOTR. I remember that I read that trilogy when my first daughter was newborn, and I spent lots of time sitting on the couch feeding, rocking, and burping her — with that tome on the couch beside me, open, so I wouldn’t have to waste a second finding my place again when she fell asleep on my shoulder. This book was less gripping, but more grown-up, and packed with food for reflection. I’m not sure I recommend it to everyone — but for Tolkien fans, definitely.