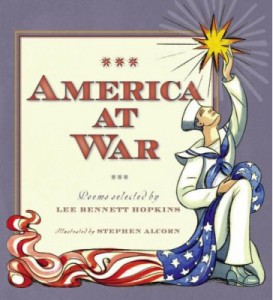

America at War

I discovered this book on the new books shelf in the children’s department at our local library. It’s a collection of poems compiled by Lee Bennett Hopkins and illustrated by Stephen Alcorn. To me, it raises some questions worth considering.

I discovered this book on the new books shelf in the children’s department at our local library. It’s a collection of poems compiled by Lee Bennett Hopkins and illustrated by Stephen Alcorn. To me, it raises some questions worth considering.

First, some description. The poems are arranged chronologically according to wars from the American Revolution to the Iraq War. They offer a wide range of authors and styles. The illustrations are bold and arresting: a maiden sewing an American flag, pausing to weep; soldiers lying in various death poses; an American eagle, clutching a gun in its talons, and a quill pen dripping blood in its beak.

My response to the book is complex. All of us hate war, and in these pages we find much to affirm that sane and humane response. Stephen Crane’s “War Is Kind,” for instance, offers a scathing comment on the sanitized or propagandistic language sometimes used to talk about it. Whitman’s “Come Up from the Fields, Father” emphasizes this disconnect between noble talk and the pathos of a family’s loss of its only son. “My sweet old et cetera” by e e cummings again exploits the irony of that contrast between spoken ideals, and a speaker lying in the mud, presumably dying.

Of course, the humane “amen” wells up when I read these poems.

At the same time, I question the honesty of Hopkins’ introductory insistence that this book “is not about war. It is about the poetry of war.” There is a fairly limited vision offered here, and a clear agenda against any war on any terms. It seems to me that “the poetry of war” must also include some examples of high-sounding language used unironically. This is part of the picture, isn’t it? (Our own national anthem, for instance.) Hopkins doesn’t trust his young readers as much as I wish he did. Children of all people have not lost their curiosity. In my opinion we can rely on them to question the “official” view of anything.

The perspective permitted in this book oversimplifies in its one-dimensionality. I hate war. Yet for centuries upon centuries, men and women have chosen to offer their lives for ideals they consider to be higher than themselves. Have they all been categorically wrong? Or do there exist ideals worth fighting — perhaps even dying — for? Does it disrespect those who have so offered themselves to consider their sacrifice a waste on any terms? Does our evaluation of war change depending on whether we look at it from the point of view of those who offer themselves willingly, or from the perspective of those who prosecute the campaign from afar? Is there such a thing as a noble motive that remains unsullied?

I think these are worthwhile, maybe necessary, questions to consider in thinking through the subject. I don’t mind asking them myself, but in a book like this I wish the poems had been allowed to. Hopkins offers Wilfred Owen’s words that “all a poet can do is warn. That is why true Poets must be truthful.” Perhaps a more complete range of perspectives would have earned this book the right to quote those words. It’s a beautiful, if limited, book. I admire the daring its editor exemplifies in attempting it. And maybe by putting it into a different category, I can redeem it entirely: this is a book that encourages young readers to dream of a world without war. In that, it can’t fail.