Dr. Thorne

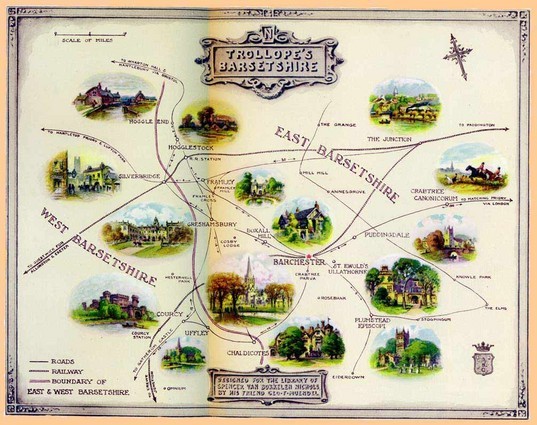

Dr. Thorne is the novel that precedes Framley Parsonage in Trollope’s chronicles of Barsetshire. I read Framley first, and though I wish I’d gotten to know Dr. Thorne beforehand, he didn’t suffer any from having been met out of sequence. In fact I liked Dr. Thorne even better than Framley Parsonage.

Dr. Thorne is the novel that precedes Framley Parsonage in Trollope’s chronicles of Barsetshire. I read Framley first, and though I wish I’d gotten to know Dr. Thorne beforehand, he didn’t suffer any from having been met out of sequence. In fact I liked Dr. Thorne even better than Framley Parsonage.

For one thing, it has more comedy. The main plot is a modified Cinderella tale involving Dr. Thorne’s niece, an heir of an old country estate washed nearly into oblivion by debt, and an old story of revenge and reconciliation. Trollope is a keen observer of human nature and social relations, and he seems to enjoy satirizing the posturing and maneuvering of his large cast of characters. He writes with sympathy of people struggling to promote their many and varied understandings of what’s the best or most loving course of action. Many of the characters are deeply flawed, but Dr. Thorne, his niece Mary, and the young Frank Gresham who loves her all emerge as genuinely admirable characters.

Much of the humor satirically exposes a time of change in England in which the accepted power trio of money, property and pedigree is beginning to break apart. Squire Gresham’s money and property are deeply indebted, but he, and more especially his wife the Lady Arabella, cling to the supposed superiority conferred by their bloodline. Lady Arabella has several conversations with both the doctor and his niece in which she intends to discourage the possibility of Mary’s marriage to Frank through what she believes to be the unquestioned notion of superior breeding. Arabella is so certain of herself that the conversations come off as comical, for the Thornes don’t share her views. The conversations mark a changing social order as well, one in which new money can make up for inferior blood, and even an individual without money, property or blood can have value. Landed families who compromise their property with debt can no longer depend on a shared assumption across all class lines that they are entitled to homage anyway.

The old order is changing, Trollope seems to say. In the case of Mary Thorne, we feel this change is attractive. She is a heroine filled with sense and nobility, and if a rigid class structure destroys her chance of marrying “up” for love, we want to see the structure toppled. But in other cases, it’s not such an appealing prospect. Louis Scatcherd is heir to a fortune, but without either breeding or natural decency and decorum. His wealth buys him a place at every table, but Trollope gives him a coarseness that makes him ridiculous and disqualifies him from our readerly affections. Ultimately he meets a tragic end, one that’s narrated with compassion but that feels like a relief partly because his fortune is left in better hands.

I really liked Dr. Thorne, a humane character with integrity and just enough vinegar to give the infuriatingly scheming Lady Arabella some resistance. Mary was at times a bit too “good” to be true (Trollope does sentimentalize his heroines), but I don’t begrudge her the happy ending. Though later in his career Trollope adopted a darker view of people, for the most part this novel has a rollicking feel that I enjoyed. I’m going to take a break from these novels for a bit and then return for more.

5 Comments

Ruth

JUST finished this the other day. I liked Miss Dunstable. Not sure how to explain her in a review, though, without giving too much away.

Janet

I like her too! — and also didn’t know how to write about her. She reappears in Framley P.

Ruth

Cool. I’m reading that one now, but I just started and haven’t gotten very far.

hopeinbrazil

So glad you liked the book. I remember liking the character, Dr. Thorne, but it’s been so long since I’ve read this that it might be time for a re-read to remind mysely why.

Barbara H.

I’ve never read Trollope, but this sounds interesting. I like the idea of the setting when the order is changing.