The Violence of Scripture

“Is this a good story, or a bad story?”

Some friends were over, and the kids were watching Prince of Egypt. They were up to the plagues, before we even got to the part where the firstborn sons are all killed, and before the Egyptian army and all their horses are drowned, when the little boy asked his question.

It’s a good question. I suppose the answer is, “It’s both — depending on your perspective.” For the Egyptians, it was a bad story. For the Israelites, it was a good story — or at least, they seemed to think so. They broke out the tambourines and sang and danced. (Remember when the Palestinians did this on 9/11?) That leads me to believe it’s a bad story for everyone. When we sing and dance over death, we are damaged people.

It’s a good question. I suppose the answer is, “It’s both — depending on your perspective.” For the Egyptians, it was a bad story. For the Israelites, it was a good story — or at least, they seemed to think so. They broke out the tambourines and sang and danced. (Remember when the Palestinians did this on 9/11?) That leads me to believe it’s a bad story for everyone. When we sing and dance over death, we are damaged people.

Lately I’ve felt like a deer in the headlights as I’ve been thinking about the many examples of violence, conquest, oppression, and in general moral atrocity in the Bible. How have I lived with this book for so long without facing it?

If you’re like me, you’ve woven an intricate dance through the Scriptures, perpetually adjusting your orientation so that these troubling scenes are in your peripheral vision. Once in awhile you don’t spin fast enough, and you come up against something unspeakable face to face:

- Egyptian bodies washed ashore to the sound of gleeful singing (I have sung along with the catchy “Horse and Rider song” that was popular in the 80’s)

- Foreign priests lured into a temple and then summarily executed

- Jericho, in which men, women, children, and animals are slaughtered

- Abraham sacrificing Isaac; Jephthah sacrificing his daughter

- War — first in a long list of “holy wars” for which God’s will is used as justification

- Slavery, rape, kidnapping (the virgins of Jabesh-Gilead are taken as prisoners of war and forced to marry the Benjamites)

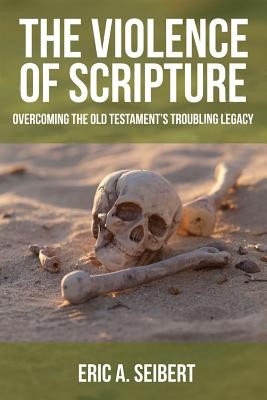

There are lots of other examples, and The Violence of Scripture: Overcoming the Old Testament’s Troubling Legacy sets these and many more before us. Author Eric Seibert calls it “virtuous” violence — in other words the violence is depicted as good and necessary in some way. Sometimes God orders it in the text (Canaanite genocide); sometimes it’s written into the laws (capital punishment); sometimes it is more cryptic or ambiguous whether God approves of it or not (Jephthah sacrificing his daughter). In several instances (Ezekiel, Nahum…) metaphors of sexual abuse are developed to illustrate God’s wrath at various cities. (I have to wonder if these texts would have even made it into the canon if they had depicted sexual violence against men.)

If you grow up in the church, you become desensitized. All the tales become fodder for abstract spiritual lessons without your having ever been encouraged to see them at their literal level. Seibert calls it “textual blindness”: “We have grown so familiar with these violent stories, and with certain sanitized ways of reading and hearing these stories, that we fail to notice what they are actually saying.” I feel a little angry about that official sanitizing. I admit it. None of us probably has to look very far back to see an example of it. As someone who has been fed these tales since childhood, I feel I haven’t been well-served.

One of the experiences that led me to home school was when my oldest daughter was in kindergarten and heard the Easter story. She exclaimed, “That’s terrible!” and then looked at me very hard, very searchingly. She was looking for confirmation that she was really hearing it right, and that her response was right. It was a teachable moment, an opportunity to affirm her natural sense of right and wrong and her tender heart. The crucifixion is terrible (and some aspects of its traditional western interpretation that emphasize God’s wrath and turning away from Jesus as he dies are equally terrible). But there are lots of other terrible things in the Bible too, and I haven’t named them for what they are. I get all up in arms about the violence people allow their young children to watch in movies, but I remain silent about the battle of Jericho. I am pro-life, yet I haven’t noticed that Abraham and Isaac, or Jephthah and his daughter (for whom no ram is provided), or the numerous children killed in biblical battles, devalue human life on a grand scale.

I believe there has been a level of conditioning that has encouraged my “textual blindness.” But ultimately I have to take responsibility for any callouses on my moral sensibility. Children don’t have that callous. And having children is among the first of the pricks that have pierced mine.

When I look down deep, I see that the way I’ve always dealt with this is by believing that the ancient Israelites simply got it wrong. This belief has been fuzzy and undefined, lurking there and producing cognitive dissonance alongside my belief that the Bible is God’s word (something I still believe, let there be no doubt). How can the God who forbade murder order it on so many occasions? How can the God who was always headed toward redemption of the whole world be so selective about the value of human life in the Old Testament? “In you all the families of the earth will be blessed,” he says to Abraham in Genesis 12. “For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son,” Jesus echoed in John 3. How can the God whose ultimate judgment on all violence and killing was pronounced from a cross where he bore it all demand it so many times?

I realize that this sounds like I’m being pretty free with Scripture. But the truth is that I know of no one who doesn’t do this already — who doesn’t write off large chunks of Old Testament morality. Today if a parent kills a child, it is universally condemned. Today when one country invades another because they believe themselves to be entitled to the land, there is an international response. Rightly so. Is this because we believe God’s moral standard has changed? Or because our cultural conditioning has changed?

Maybe it seems to put us in less stable territory to suggest that there are things in the Bible that reflect the human vessels through whom God spoke, but it’s no less stable than it had ever been. If we believe in inspiration of Scripture, be acknowledge a level of cultural conditioning in the human minds through which God works as he conveys his word. I guess this book has made me think seriously about moving the boundaries I’ve placed circumscribing the divine word within the human vessels. It’s a smaller territory than I thought — unless I believe that God’s moral sensibility is accurately reflected in some of these stories.

I am amazed by the humility of a God who is willing to be so misrepresented, willing to work with such desperately misguided and self-involved creatures as we are. In Jesus we see a God willing to humble himself “even to death on a cross.” In Scripture, perhaps we see a God equally willing to humble himself to violence done to his character through our human terms. He overcomes both sets of strictures: the cross, by returning to life; the violence in the Bible, by managing to convey a clear redemption narrative across the whole sweep of history and the intricate and often confusing polyphony of the biblical writers. Though I am beginning to believe he is victimized by having words put into his mouth that he didn’t say in the Old Testament, the events of history (Jesus) and the fulfillment of prophecy (the promised Messiah, the suffering servant) indicate that he triumphs over these limitations and his character is revealed in the person of Jesus. Enough truth gets through to validate the Bible’s overarching message.

I keep veering away from talking about The Violence of Scripture.

Honestly, I’m not sure I recommend this book. It is helpful in a limited way. It locates the hard parts of the Bible very well, and it assures us that we’re right in seeing serious confusion in the moral picture of the Old Testament. Seibert also lays out a number of historical events in which the Old Testament has been used to justify atrocities.

But I part ways with Seibert in several regards. For one thing, what seems to be his primary motivation is preventing further misuse of Scripture to justify violence, whereas my interest is in clarifying the character of God. For another, Seibert’s solution is changing how we read Scripture to “reading nonviolently.” This involves using the ethics laid out in some of Scripture — what he calls its “normative” pattern — as a lens through which to judge what we read, and I’m fine with that. But he also recommends various other “reading strategies” that I am more dubious about: filling in the gaps in the stories with our own imaginative material; using literary deconstruction to make sophisticated analyses of the ancient texts; censoring the Bible for children. (In this last item I wouldn’t argue that all the stories in the Bible are suitable for children, but I favor a developmentally appropriate approach that introduces different parts of the Bible at different ages rather than censorship or rewriting. For instance, at one point Seibert recommends excising the verses where David says God is with him when he fights Goliath, then following up the story with lots of imagining how Goliath might have felt.)

To me the elephant in the room with a book like this is, who needs a holy book if you know better than it does? Who needs a holy book that has to be censored and heavily superscribed with your own enlightened editorial judgments and additions? And who, certainly, needs a holy book that can’t be understood without the techniques of postmodern literary theory? At times Seibert assures us that there is much to be appreciated in the Bible, and he speaks from a believer’s perspective. But overall I found his attitude toward it to be too condescending to be of much use.

In the end it’s the Holy Spirit — who, we believe, inspired the biblical writers in the first place — to whom we must appeal for help in understanding his book. I don’t believe these matters are intellectual so much as spiritual. God will help us to push all the way through to meaningful answers. (He has already begun to do this.)

In the end it’s the Holy Spirit — who, we believe, inspired the biblical writers in the first place — to whom we must appeal for help in understanding his book. I don’t believe these matters are intellectual so much as spiritual. God will help us to push all the way through to meaningful answers. (He has already begun to do this.)

I can look back and see what I believe to be a long accumulation of answered prayers in my life, many of them prayers for understanding. But one stands out. It was when I was in my twenties and had gone through a period of rebellion, and now I was repenting. I regretted the way I had spent that year and realized that I couldn’t make things all better; such damage as was done, was done. But God forgave me. I remember crying off and on for several days in a curious combination of grief and joy, sorrow and grace. It’s the most real, most powerful marker in my spiritual life. A church kid, I saw my sinfulness at last. And I knew God’s love and grace. That’s who he is: he is beyond intellectual precept or emotion, and he gives us his Spirit to meet us, to provide for every need of our souls. Surely one such need is for wisdom regarding his written word, and I believe he is the one who clarifies all that’s confusing or false.

Lent begins today. I guess what I’m giving up is some of my security in how I think of Scripture. I’m giving it back to God. I am probably giving up some of my security in my community too, because these are very uncomfortable issues and questions for evangelicals. These are the kinds of questions that can lead one to stumble in their faith. Yet I still believe a faith that never works through them is ultimately in more danger. God asks for more than mere intellectual assent; he asks for our trust. That’s what makes it so important to face these questions honestly. God is big enough.

3 Comments

Barbara H.

I have to admit I have wrestled with this issue, too. I think I mentioned before that I didn’t necessarily have a problem with big things like hurricanes or tornadoes taking out scores of people in the sense that God is the author of life and He is the One to say when it ends. Whether He brings people to death individually or in masses doesn’t make much difference except that the big events make cause people to ponder more. I think that’s one purpose of death. Ecclesiastes 7:2 says, “It is better to go to the house of mourning, than to go to the house of feasting: for that is the end of all men; and the living will lay it to his heart.”

But I have struggled with more things like the OT heroes or armies taking lives or the commands to stone people for certain crimes. I do believe in capital punishment: I think God set up the reason for that in Genesis 9:5-6: if you take a life, your life is forfeit. Maybe God sending an army against another country is capital punishment on a larger scale? Maybe that “fit” in that time and culture because all the world over, different groups of people sought to fight and conquer one another? Maybe what people were supposed to realize about stoning was what Jesus said about the woman taken in adultery with “Let him who is without sin among you cast the first stone” — if we stoned everyone who sinned, there would be no one left.

I’ve wrestled with violence, too, with having boys whose games from early boyhood to teen video games involve conquering someone. Even if you don’t buy them guns and don’t watch violent movies, they make guns out of sticks and “shoot” each other. “Conquering” isn’t a bad thing — in any story of good vs. evil, it’s going to get messy. But on the other hand, one note God made about the world before the flood was that “the earth was filled with violence,” and in Psalm 11:5b it says, “him that loveth violence his soul hateth.” There is obviously a difference between, say, the battles in Narnia as opposed to the senseless violence of mass murderer who seems to kill just for the pleasure of it. But in other places it is hard to know where to draw the lines.

I don’t know all the answers to these things, but I agree that part of the solution is to trust Him. I can’t fathom anyone advocating “filling in the gaps in the stories with our own imaginative material” and such. As you said, “who needs a holy book if you know better than it does?”

Janet

I appreciate your thoughts on this, Barbara.

This book raised my awareness in a new way, and though I didn’t think all the reading strategies it suggested made sense, I’m grateful for the way it challenged me and made me face things in the Bible that I wasn’t fully aware of despite my familiarity. There is something to the “textual blindness” idea for me!

hopeinbrazil

I know you are right that those of us who have grown up on the church tend to skim over these difficult passages (or accept them without thinking). God helping us, we should be able to look at ALL scripture honestly and humbly. Thanks for the thoughtfully written post.