Now I Remember: The Autobiography of Thornton W. Burgess

Sometimes you can enjoy a series of books, but grow disillusioned when you read the author’s biography. (This happened to me when I read Elizabeth Goudge’s autobiography.) But in Thornton Burgess’s case, I find my respect and liking for the man greatly increased by reading his autobiography. And I am drawn back to the stories of the Green Meadows and the Green Forest now that I have learned more about their back story and motivation.

Sometimes you can enjoy a series of books, but grow disillusioned when you read the author’s biography. (This happened to me when I read Elizabeth Goudge’s autobiography.) But in Thornton Burgess’s case, I find my respect and liking for the man greatly increased by reading his autobiography. And I am drawn back to the stories of the Green Meadows and the Green Forest now that I have learned more about their back story and motivation.

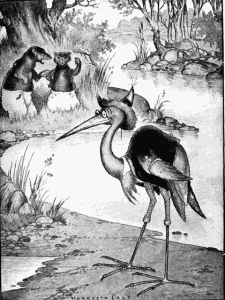

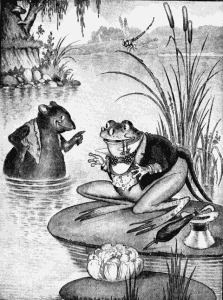

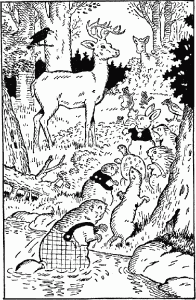

I grew up with the Thornton Burgess books. My parents passed some on to me, and my grandmother gave me some new ones for Christmas one year. My favorite was Lightfoot the Deer, but over the years (and more recently, with my daughters) I’ve read the respective adventures of Paddy the Beaver, Johnny Chuck, Grandfather Frog, Peter Rabbit, Longlegs the Heron, Mr. Mocker, Chatterer the Red Squirrel, and The Burgess Bird Book. I have to say that though I enjoyed them as a child, I took them in fairly small doses. They are written in a sentimental style, and the animals are given human characteristics — including human speech. The pictures by celebrated illustrator Harrison Cady are very distinctive, but they never really appealed to me.

Since reading the books with my daughters I’ve noticed that underneath the stylistic trappings, there is quite a bit of real nature knowledge. As we come upon different animals in our travels, it’s becoming a reflex to reach first not just for the Handbook of Nature Study or an animal encyclopedia, but for a Thornton Burgess book as well. And we find ourselves referring to the “folk in fur and feathers” (as Burgess calls them) around the yard by his names for them: Chatterer, Happy Jack, Sammy Jay, and so on.

Since reading the books with my daughters I’ve noticed that underneath the stylistic trappings, there is quite a bit of real nature knowledge. As we come upon different animals in our travels, it’s becoming a reflex to reach first not just for the Handbook of Nature Study or an animal encyclopedia, but for a Thornton Burgess book as well. And we find ourselves referring to the “folk in fur and feathers” (as Burgess calls them) around the yard by his names for them: Chatterer, Happy Jack, Sammy Jay, and so on.

Now I Remember was published in 1960, when Burgess was 86. Despite the distinctive, grandfatherly voice that pervades the stories, I really had no idea who the man behind them was. Born in Sandwich, Massachusetts and a self-identifying lifelong Cape Codder no matter where else he lived, he was an only child who lost his father in his first year of life. As a boy he helped earn money by collecting plants, tending cows, and trapping muskrats, and these outdoor rambles laid a foundation of nature observation that later blossomed into his best-known tales. “Studying the wild things and their ways that I might better outwit and kill them, I was with complete unawareness laying the foundations for my lifework, which began happily when I put away the gun for camera and typewriter,” Burgess explains.

He went to business school for a year, but that was the extent of his post-high school education. As a writer he began by writing advertising copy; the nature stories began when his 5-year-old son was staying with relatives (he was married twice; only a year into marriage, his first wife died at the birth of their son), and he would send him stories about the “little people” of the Green Meadows and Green Forest and Smiling Pool. Burgess wrote 15,000 stories for newspapers and magazines and well over 100 books. An amateur naturalist, he built on the foundation of his early years of firsthand observation through study and field research, always aspiring to accuracy and avoidance of becoming what President Teddy Roosevelt termed “nature fakers.” Though his writing career began in the desire to simply entertain and make a living, he quickly realized that his books had educational value, and he became a strong advocate for nature study and conservation. He worked to pass laws protecting migrant wildlife, and started various clubs associated with his stories and radio programs with rewards for conserving behavior and nature study: the Bedtime Stories Club, the Green Meadow Club, the Radio Nature League, and even the Happy Jack Squirrel Saving Club for children buying thrift stamps and bonds during World War I.

He went to business school for a year, but that was the extent of his post-high school education. As a writer he began by writing advertising copy; the nature stories began when his 5-year-old son was staying with relatives (he was married twice; only a year into marriage, his first wife died at the birth of their son), and he would send him stories about the “little people” of the Green Meadows and Green Forest and Smiling Pool. Burgess wrote 15,000 stories for newspapers and magazines and well over 100 books. An amateur naturalist, he built on the foundation of his early years of firsthand observation through study and field research, always aspiring to accuracy and avoidance of becoming what President Teddy Roosevelt termed “nature fakers.” Though his writing career began in the desire to simply entertain and make a living, he quickly realized that his books had educational value, and he became a strong advocate for nature study and conservation. He worked to pass laws protecting migrant wildlife, and started various clubs associated with his stories and radio programs with rewards for conserving behavior and nature study: the Bedtime Stories Club, the Green Meadow Club, the Radio Nature League, and even the Happy Jack Squirrel Saving Club for children buying thrift stamps and bonds during World War I.

My daughter is sitting here as I type this, and I asked her what she likes best about the Burgess stories. She replies, “The animals mostly get along. There is real nature in them, but the animals get along.” This is intentional, as Burgess explains. Children learn quickly enough of the cruelty in the world. He felt strongly that in stories for children they should not be treated to the “realism” of their favorite characters getting eaten. That’s why Reddy Fox never gets Peter Rabbit. At one point in Burgess’s lifetime, an editorial gently poked fun at this by asking, “When Does Old Man Coyote Eat?” But on the whole the safety of the fictional world, though not totally realistic, is one of the features that held readers so devotedly.

I had mixed feelings about some things. These days it’s hard to imagine stories as propoganda to get children to invest in war efforts. But at the same time I found myself wistful for the kind of national unity and community that existed then, and for the moral consensus that surrounded the war effort. We live in a much more ideologically fragmented age — less naive, but with a knowledge that has come at some cost.

I also hesitate at Burgess’s repeated assertion that nature stories are ideal vehicles for conveying morals because of children’s innate sense of superiority to animals. Again, we live in a different age when it’s not fashionable to think in such a tiered way about nature; ecosystems and webs of life are inherently more democratic than superior and inferior species. Yet I’m also a Christian who remembers that the first responsibility humans are given in Genesis is to steward the Creation. There is a hierarchy of sorts; who can deny that humans display qualities that are unique among all species? The ability to reason and reflect and alter our environment can be used for good or ill, and can be exercised with the humility that comes with recognizing that we are dependent on the health of the world around us. So I found myself qualifying and revising some of Burgess’s views.

Even though I felt some of these differences, I found Burgess to be an extremely gracious personality, and my strongest impression as I close the book is liking for him. This book includes an account of events in his literary life, description of his writing habits, memories of childhood, various philosophies of life, personal and professional associations, and excerpts of letters from readers over the years that he has accumulated in a scrapbook. It could have come off as self-adulation, but it doesn’t. Instead what comes across is his great appreciation for his readers, and the enormous encouragement and inspiration they provided him. He sees himself as indebted to them.

Even though I felt some of these differences, I found Burgess to be an extremely gracious personality, and my strongest impression as I close the book is liking for him. This book includes an account of events in his literary life, description of his writing habits, memories of childhood, various philosophies of life, personal and professional associations, and excerpts of letters from readers over the years that he has accumulated in a scrapbook. It could have come off as self-adulation, but it doesn’t. Instead what comes across is his great appreciation for his readers, and the enormous encouragement and inspiration they provided him. He sees himself as indebted to them.

I come away from Now I Remember knowing I would have been one of the many who loved this author and felt a sense of personal connection with him. His stories were a part of daily life in the newspapers for thousands of people and provided not just nature knowledge, but a sense of stability and decency in a rapidly changing world. His impact is much greater than I knew.

3 Comments

hopeinbrazil

Lovely review. We read Burgess when we homeschooled, but I didn’t know anything about him.

Carrie, Reading to Know

(I’ve had this post up for days waiting to be able to read through it!)

I know what you mean about how you can sometimes lose interest in the author’s works once you know more about the author themselves. Glad to know it’s not the case with this one.

I’ve only read one of Burgess’s books and I wasn’t overwhelmed by it. I wasn’t put off by it either and wouldn’t mind reading them with my kids. Of course, if I’m going to read more of his books, I’d be curious to learn more about him as well. This book sounds like a winner on the whole. Glad you posted about it! Thanks for the info!

Janet

Yes, reading Burgess wasn’t overwhelmingly positive or negative for me either. I probably would have written him off as an outdated author if not for the pleasure my daughters seem to take in his books. It made me take a second look, and they’ve grown on me. I liked getting to know him a bit in this bio.