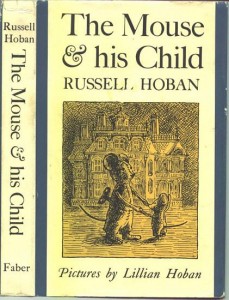

The Mouse and His Child

Back when I did my Celebrate the Author Challenge post on Russell Hoban, I learned that he was far more than just the author of the Frances books. These, and Harvey’s Hideout, were the ones I was familiar with from my own childhood, but Hoban has any number of novels and stories for grown-ups on his list as well.

Back when I did my Celebrate the Author Challenge post on Russell Hoban, I learned that he was far more than just the author of the Frances books. These, and Harvey’s Hideout, were the ones I was familiar with from my own childhood, but Hoban has any number of novels and stories for grown-ups on his list as well.

The Mouse and His Child is classed as a children’s tale, and it’s Hoban’s first full-length novel. Written in 1967, it’s also his last collaborative enterprise with then-wife Lillian Hoban, who drew the pictures for the first version. The story went out of print, then came back into print with illustrations by David Small.

I became interested in it after reading Hope’s review. She called it “a very adult fairy tale,” and having read it, I agree. I’m not sure I could read this one to my children… I doubt that they would tolerate its darkness. But it leaves me with a lot to think about.

There are plenty of stories out there about the lives of toys. This one is unique in that it doesn’t include a single real child. Owners are in no way a part of the identity of the toys in this story. The main characters are a wind-up mouse and his son, attached at the hands and made to dance in a circle. The story begins in a toy store, a place of security and beauty, but the mouse and his child soon find themselves loose in the wide world. They endure hardship and adventure in which events — many of them sad or cruel, some of them violent — teach, strengthen, and change the toys. The first change for them is that through an accident they no longer dance in a circle, but make forward progress. This turns out to be a good thing as their quest develops from mere survival instinct to the desire to become self-winding, and the final outcome has to be one of the truly happy endings of all children’s literature.

I’ve used the words “sad,” “cruel,” and “violent.” For one thing, there’s quite a bit of nature red in tooth and claw in this story. There’s enslavement. There’s selfishness, and war. And there’s villainy, most notably in the figure of Manny Rat, Lord of the dump. In all honesty this was probably not the best time in my life to be reading a book that suggests, as the mouse child says, “There’s nothing on the other side of nothing but us,” and at one point I almost closed it for good. But I’m glad I didn’t, because endurance and love and courage do eventually win out.

I have to add that it’s also gracefully written, and sprinkled with wit and unsentimental humor. It reminded me a little of E.B. White, though overall it’s more philosophical and symbolic than any of the White stories I’ve read. It’s mainly in the characterization that I hear the same wry, shrewd eye for people. Here’s an example, from a section in which the mouse and his child become briefly entangled with a pair of crows who run a travelling drama troupe known as The Caws of Art:

A large crow came walking out of the pines and cocked his head to listen. A tall, well-set-up bird, he wore his great black, glossy wings in the manner of a cloak thrown carelessly over his shoulders, and he had what his wife and fellow actors admiringly described as “presence.” Wherever he was, he simply seemed to be there more intensely than any other bird.

Here’s another example of compelling characterization, from our introduction to Manny Rat. This one’s not at all funny:

He wore a greasy scrap of silk paisley tied with a dirty string in the manner of a dressing gown, and he smelled of darkness, of stale and moldy things, and garbage. He was there all at once and with a look of tenure, as if he had been waiting always just beyond their field of vision, and once let in would never go away.

I was very intrigued by this book. As an introduction to the world beyond Frances, I recommend it to the curious. Really, for anyone interested in the kind of story that offers unexpected insight into what it means to be human, this is a worthy read. It’s about a pair of creatures who don’t know why they’re here or how to find their way, but who value their lives dearly and waste no piece of the knowledge they glean through their experiences. It’s meaningful on many layers.