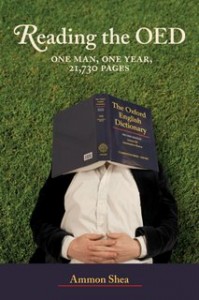

Reading the OED

There’s a word for me: Anonymuncule (n.) An anonymous, small-time writer.

There’s a word for me: Anonymuncule (n.) An anonymous, small-time writer.

Turns out there are words for all kinds of things, more words than any of us knew about. Ammon Shea discovered this in his year-long odyssey through the Oxford English Dictionary:

If you were to sit down and force yourself to read the whole thing over the course of several months, three things would likely happen: you would learn a great number of new words, your eyesight would suffer considerably, and your mind would most definitely slip a notch. Reading it is roughly the equivalent of reading the King James Bible in its entirety every day for two and a half months or reading a whole John Grisham novel every day for more than a year. One would have to be mad to seriously consider such an undertaking. I took on the project with great excitement.

This book is much more readable than many of us would find the OED. Shea writes a chapter for each letter of the alphabet, culling a few of the most unusual or striking or funny words he discovered, and prefacing his lists with short essays on various topics. He describes his apartment full of dictionaries, his experiences searching for a setting without distractions (he ends up in the Hunter College library basement), his experiences and reflections on reading and being a vocabularian in general.

I laughed out loud many times, not just at the obsolete and far-out words, but at Shea’s dry commentary. At first I felt inspired. But after awhile the sarcasm and repeated jokes about Shea’s antisocial inclinations started to irritate me.

Nor could I relate to the joy of dictionary-reading. Not to be an ultra-crepidarian, but I don’t see the appeal. Reading a dictionary merely to collect (not, he points out several times, to use) words seems to miss the point in the same way the intellectual in Lewis’ The Great Divorce does when he comes to love the process of inquiry for itself, rather than as a way of seeking answers. Even Samuel Johnson notes in the preface to his dictionary in 1755,

I am not yet so lost in lexicography as to forget that words are the daughters of earth, and that things are the sons of heaven. Language is only the instrument of science, and words are but the signs of ideas.

Obviously I’m missing a point somewhere. Though I like Shea’s thoughts about books vs. computers (the OED is available online now), I guess I view reading (and a few other things) differently than he does in some ways that turn out to be important.

The truth is, though, I read this from cover to cover, and for the most part I enjoyed it. It does raise a number of interesting points about the evolution of words, and manages simultaneously to amuse and inform. Best of all, it took a couple of days to read; Shea has “read the OED so you don’t have to.” I’m not likely to pick up the real OED anytime soon, but for an entertaining introduction this is definitely the book to read.