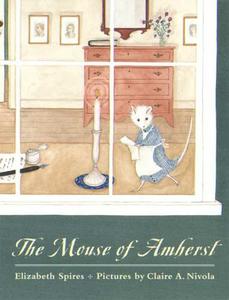

The Mouse of Amherst

Some time ago, another blogger mentioned The Mouse of Amherst in a Poetry Friday post. I ordered it immediately, but not until yesterday did the right time come for Elizabeth Spires’ 61-page imaginative introduction to Emily Dickinson, accented by Claire Nivola’s delicate drawings. The ultimate proof came at the end, when my 8-year-old exclaimed, “Let’s read some of her poems!”

Some time ago, another blogger mentioned The Mouse of Amherst in a Poetry Friday post. I ordered it immediately, but not until yesterday did the right time come for Elizabeth Spires’ 61-page imaginative introduction to Emily Dickinson, accented by Claire Nivola’s delicate drawings. The ultimate proof came at the end, when my 8-year-old exclaimed, “Let’s read some of her poems!”

The Mouse of Amherst is named Emmaline. She lives is the wainscoting in Emily Dickinson’s bedroom, and although she owns a quill pen, an inkwell, and a notebook, she values them chiefly as decorations. It’s when she observes the poet in action, reads one of her poems, and begins exchanging poetry with Emily herself that she realizes not only the meaningfulness and purpose of words, but her own unplumbed poetic gifts.

Emmaline’s point of view creates a fitting air of mystery around this writer neighbors referred to as “the Myth.” The mouse is bewildered at times as she observes Emily, but always speaks out of a deep sense of kinship with her. As mouse and poet exchange their thoughts in writing, poetry is depicted as a vessel that catches the overflow and the cross-currents of experience. The poems chosen — actual poems by Emily Dickinson, as well as those written by Emmaline — do not condescend. Enough reaction to the poetry is given to begin the process of interpretation, but it is not analyzed or flatly explained. In the end, the ambiguity is intact, but not intimidating to a young reader.

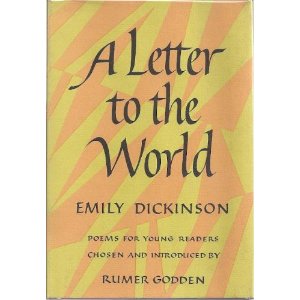

I wished I had read Rumer Godden’s introduction to A Letter to the World: Poems for Young Readers before reading Mouse instead of after. It provides a brief biographical review that would have made certain scenes in Mouse more intelligible. It would have been better, for instance, if I had brushed up beforehand on Colonel Higginson’s visit to the house in Amherst as a potential publisher of Dickinson’s poetry. But even without the benefit of outside knowledge, The Mouse of Amherst creates a memorable portrait of this reclusive philosopher who would lower gingerbread from her window in a basket to the children playing below, who composed nearly 2,000 poems bound together with twine into tiny booklets, and who described her own literary sensibility by saying,

I wished I had read Rumer Godden’s introduction to A Letter to the World: Poems for Young Readers before reading Mouse instead of after. It provides a brief biographical review that would have made certain scenes in Mouse more intelligible. It would have been better, for instance, if I had brushed up beforehand on Colonel Higginson’s visit to the house in Amherst as a potential publisher of Dickinson’s poetry. But even without the benefit of outside knowledge, The Mouse of Amherst creates a memorable portrait of this reclusive philosopher who would lower gingerbread from her window in a basket to the children playing below, who composed nearly 2,000 poems bound together with twine into tiny booklets, and who described her own literary sensibility by saying,

If I read a book, and it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?

An excellent question, that. How do you “know it”?

Colonel Higginson told Emily Dickinson her poems were “alive but spasmodic,” and “uncontrolled.” Rumer Godden more rightly describes

this style like glancing light, the paradox of an odd flippancy about serious matters like death and God, with an immense awareness of their insoluble mystery. There [is] an unpretentious camaraderie.

Spotlighting this “unpretentious camaraderie” is what The Mouse of Amherst does best. Elizabeth Spires manages to introduce the large issues of the power, mystery, and relevance of poetry without losing sight of its human face. That’s quite an achievement.

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away

Nor any Coursers like a Page

Of prancing Poetry –

This Travel may the poorest take

Without offense of Toll –

How frugal is the Chariot

That bears the Human soul.–Emily Dickinson