The Golden Key

These days I use the library as much as possible, but every once in awhile I come across a book I simply must have. George MacDonald’s The Golden Key is such a book. It’s an allegory, written for children and only 78 pages long. But it’s compact and mystical enough that I know I’ll want to return to it often. And I know there are scenes in it I’ll never forget.

These days I use the library as much as possible, but every once in awhile I come across a book I simply must have. George MacDonald’s The Golden Key is such a book. It’s an allegory, written for children and only 78 pages long. But it’s compact and mystical enough that I know I’ll want to return to it often. And I know there are scenes in it I’ll never forget.

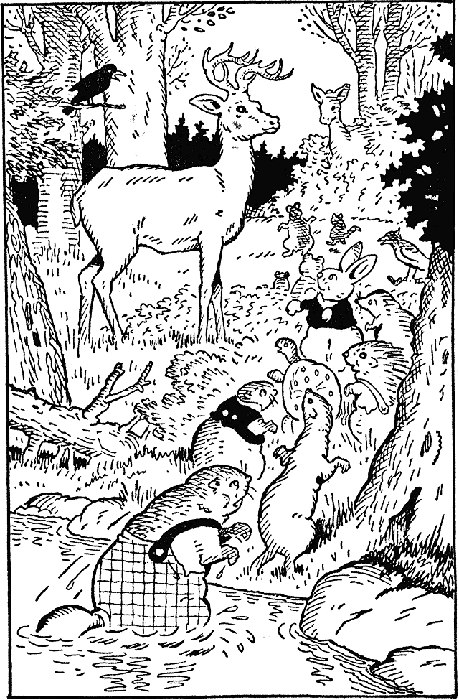

This one, for instance, when Tangle (the heroine) and Mossy (the hero) make their way across a wide plain covered with shadows on their way to find the source of the rainbow, to which Mossy has found the golden key:

They had never seen any space look like it… It was no wonder to them now that they had not been able to tell what it was, for this surface was everywhere crowded with shadows. It was a sea of shadows… No forests clothed the mountain-sides, no trees were anywhere to be seen, and yet the shadows of the leaves, branches, and stems of all various trees covered the valley as far as their eyes could reach… As they walked they waded knee-deep in the lovely lake. For the shadows were not merely lying on the surface of the ground, but heaped up above it like substantial forms of darkness, as if they had been cast upon a thousand different planes of the air. Tangle and Mossy often lifted their heads and gazed upwards to descry where the shadows came; but they could see nothing more than a bright mist spread above them, higher than the tops of the mountains, which stood clear against it.

It’s not long before the two begin to discern the shadows not just of objects of nature, but of an unfolding human drama:

Now a wonderful form, half bird-like half human, would float across on outspread sailing pinions. Anon an exquisite group of gambolling children would be followed by the loveliest female form, and that again by the grand stride of a Titanic shape, each disappearing in the surrounding press of shadowy foliage. Sometimes a profile of unspeakable beauty or grandeur would appear for a moment and vanish. Sometimes what seemed lovers passed… Sometimes wild horses would tear across, free, or bestrode by noble shadows of ruling men. But some of the things which pleased them most they never knew how to describe.

About the middle of the plain they sat down to rest in the heart of a heap of shadows. After sitting for a while, each, looking up, saw the other in tears: they were each longing after the country whence the shadows fell.

‘We must find the country from which the shadows come,’ said Mossy.

‘We must, dear Mossy,’ responded Tangle. ‘What if your golden key should be the key to it?’

That’s more than I usually quote, but part of the reason I blog is to remember such passages.

It’s not just that I can trace the line from that passage backward to Plato, or forward to C.S. Lewis. It has more to do with what my father describes of his conversion. As a young man who believed Jesus was a commanding teacher but not the son of God, he remembers an old man directing his attention to Psalm 22. It’s a prophetic Psalm that describes crucifixion, written by David about two centuries before crucifixion was practiced. It bumped around in his brain for years, along with a growing collection of irreconcilable, unpigeonhole-able data, which paved the way for his eventual surrender to the truth of Jesus’s claims about who he was.

George MacDonald’s tales have a similar effect. The edition I read contained an afterword by W.H. Auden, who points out wisely, “To hunt for symbols in a fairy tale is absolutely fatal. In The Golden Key, for example, any attempt to ‘interpret’ the Grandmother or the air-fish or the Old Man of the Sea is futile: they mean what they are.” To me, this doesn’t mean that MacDonald’s stories have no symbolic significance; it means that they have many facets of meaning. The imaginative vision in this story gets somehow under, or behind, my rational understanding of certain important realities and sheds a vital — and very beautiful — light on them.

The flyleaf quotes J.R.R. Tolkien’s observation that “The magical, the fairy story… may be made a vehicle of mystery. This is at least what George MacDonald attempted, achieving stories of power and beauty when he succeeded, as in The Golden Key.” Though there are things my daughters won’t “understand” here (there’s plenty I don’t “understand”), I can’t wait to read it to them and, in so doing, give them a gift — a golden key that stirs their longing for a larger, more glorious world.