iGen: Reaping what we sow

Since I didn’t know what iGen was, the subtitle is what attracted me: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy — and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood (and What That Means for the Rest of Us). I put the book on hold at the library awhile ago, and for the past few weeks it has alternately horrified, intrigued, and antagonized me. Social psychologist Jean Twenge has compiled a raft of statistics about the post-millenial generation born since 1995, and as her moniker “iGen” indicates, she interprets them largely as a result of the iPhone’s influence. iGen’ers have grown up in an age when our screen-centric gadgets are everywhere and contaminate almost every aspect of our lives. Among the many variables considered in studying the differences between generations, you could certainly make a case for the explosion of screen tech as a — or the — defining factor for iGen.

The book presents mostly disturbing findings, many of them pointing to a longer growing-up trajectory for iGen. Characteristics include:

The book presents mostly disturbing findings, many of them pointing to a longer growing-up trajectory for iGen. Characteristics include:

- Less in-person social life, and more online social interaction and recreation

- More depression and suicide

- Fewer teens getting their driver’s licenses or part-time jobs

- Less partying, experimentation with alcohol or sex, and time apart from parents

- Fixation on safety, not just physically, but emotionally (hence terms like “microaggression,” “trigger warnings,” “safe spaces” on college campuses)

- Later (and less) marriage

- A focus on lucrative, rather than meaningful, work

- Political independence, closer to the libertarian perspective than either of the other major parties

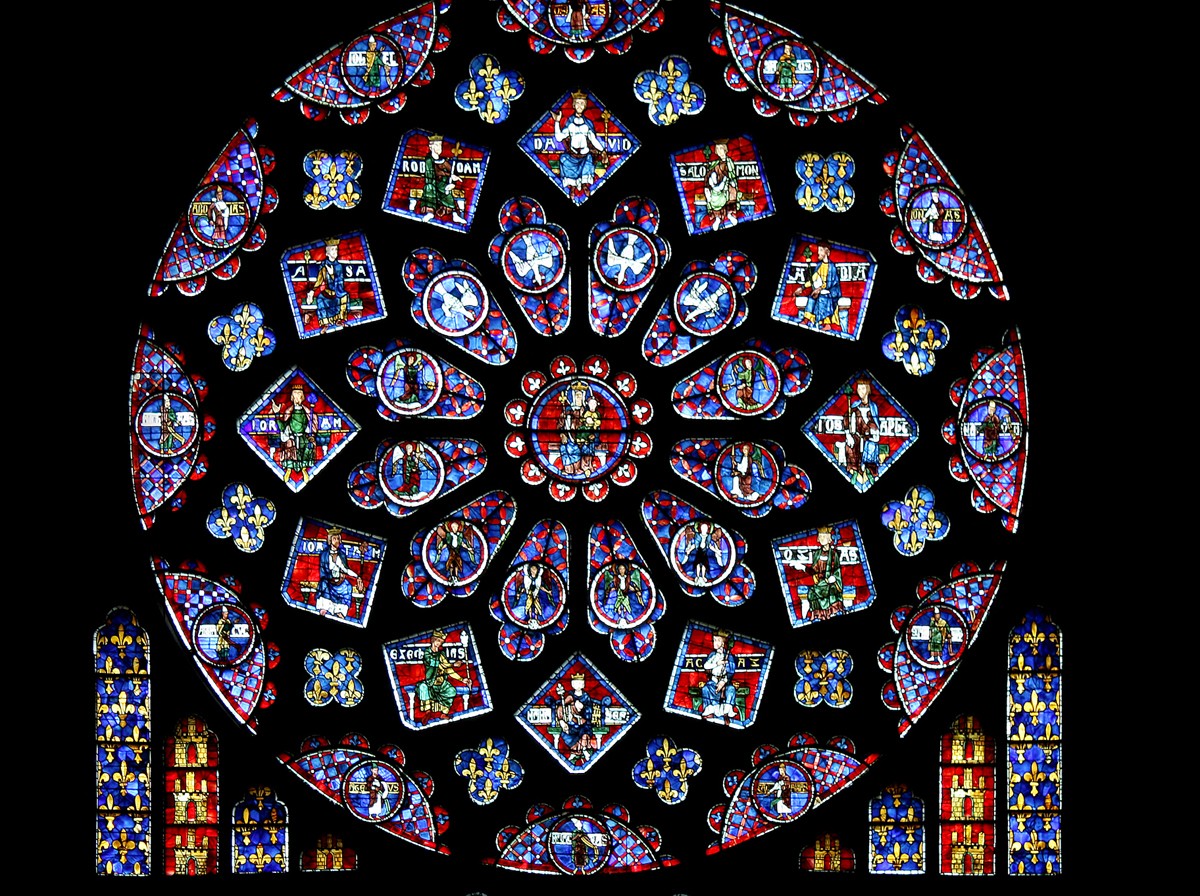

- Distrust of institutions (including religious institutions) and a belief that Christianity needs an update to make it more “inclusive”

- A steep decline in reading

The evidence Twenge uses in her discussion makes for interesting reading. Sometimes it’s heartbreaking, as teens discuss their largely solitary lives. The book is aimed at a general audience rather than an academic one, so although it contains innumerable graphs and statistics, the text is easy to navigate. After unpacking the results of the major studies that concern her, Twenge concludes with a chapter entitled “Understanding — and Saving — iGen.”

My reactions, as I’ve already noted, ran the gamut: reflection, sorrow, anger. iGen has certainly been informative to me about the generation my kids belong to. Thanks to their largely tech-skeptical mother, my kids are exempt from a lot of the characteristics that seem to define iGen. They haven’t grown up with screens and social media. Such friendships as we have locally are real and not virtual. We still respect books and read them. As I read this one, I was struck by how even though the net results are positive for my kids, being on the outskirts of the iGen zeitgeist might make for a lonelier life. Then again, there are other screen refugees out there. One of them, an 18-year-old young woman, is quoted in the last chapter after she has given up social media entirely: “Sometimes there will be a 10-minute-long conversation where I can’t participate because I didn’t see that post or I didn’t watch that video, but I’d rather not anyway. If I want to get to know someone, I don’t want to know the version of themselves that they artificially created and posted online… How important is it really to know what Mary posted yesterday on Instagram?”

Home educators are often seen as overprotective, and we may worry that we aren’t pushing our kids hard enough to be independent. But it appears that independence among young people is in decline generally. I’m tempted to say all parents seem to be overprotecting their kids, but turning them loose on the internet can’t really be called protection. iGen’ers are being protected from the risks that come from venturing out physically and inter-personally, but not from those inherent in the net: porn, bullying, addiction, and a generally warped view of human relating and self-worth. Online social life seems to take the built-in vulnerabilities we all have and amplify them rather than satisfying them. Extreme emotional fragility is one of many potentially harmful results.

That’s a main take-away, for me, from the book: we reap what we sow, especially as parents. The internet is a relatively new development, and iGen reflects certain parenting practices that seem to have developed in response to its quick dominance. Many of the downsides of being an iGen’er could have been — and perhaps still can be — prevented by parenting choices. For example, if you have a 20-something son who does not work, lives at home, and games all day (this describes 25% of early 20-something men), you could initiate positive change by insisting that he grow up: get a job, seek an education, move into his own place. If you have a daughter crushed by social media bullying, pull the plug on it and try to figure out how else to help. We reap what we sow. Parents sow human beings. Why would we be passive about the influence online experience can have?

Some of the recommendations in the last chapter made sense to me: limit smartphones to older teens, choose and monitor which social media platforms your kids use, teach kids how to evaluate sources, use apps that limit time spent on certain sites, and use filters to prevent your child from seeing porn. Try to combat what Twenge calls the “in-person deficit” by encouraging real, rather than virtual, interaction.

But some of the recommendations made me mad. For instance, Twenge thinks college textbooks shouldn’t include so much information and need to be made easier. Why dumb down the standard? This seems backward — like telling a baby, “Walking is hard, so we’re going to redesign the house so you can live lying down all day.” Being able to read a book involves the ability to listen to someone else for awhile; some of the teens interviewed in this book seem unable get beyond themselves long enough to do that, and giving up doesn’t help them.

Similarly, recommending that employers tout the safety of their businesses and interact with iGen’ers like encouraging, supportive parents does nothing to foster the kind of maturity and wisdom needed to navigate life. One of the main deceptions of virtual reality is the sense of control it can perpetuate. In real life, there are plenty of variables over which we have no control at all. The iGen’ers in this book seem to react to adversity by being offended, but sooner or later we all have to develop courage. Coddling does nothing to prepare someone for this (nor, by the way, does it fill the need the employer has when s/he hires someone to do a job…).

Pick up iGen if you’re looking for a thought-provoking read that will take you across the complex, maddening ground of modern life. It’s an engaging read that will spark varied reactions, but ultimately it takes you to the important questions about how we live.

3 Comments

Amy @ Hope Is the Word

Thanks for the review! It’s such a sticky decision, isn’t it? Sometimes I wish I (and therefore my children) had been born a decade earlier to avoid all this as children.

Janet

Yes! There are lots of decisions and distinctions to be made regarding kids and the internet/iphone, and we have no “when I was a kid, we handled it this way” to rely on… We don’t have the benefit of past models.

J. W.

Good review. Thanks for sharing! We have other books by this author, but I will get this one now as well.