Bartleby the Scrivener

Have you ever read this?

Have you ever read this?

Herman Melville’s enigmatic tale about a law scrivener who comes to an office on Wall Street was part of an American lit class in college. I loved this puzzling, bleak story about the law copyist, his employer, and the inscrutable sentence that makes up almost Bartleby’s entire vocabulary: “I would prefer not to.”

I’ve reread it several times now, and it draws me in every time. The narrator is a well-off middle-aged lawyer with several copyists in his employ. He hires Bartleby, who at first does a bang-up job as a scrivener. He writes diligently and neatly from morning to night and has no apparent vices, unlike Turkey and Nippers, the other two scriveners in the office.

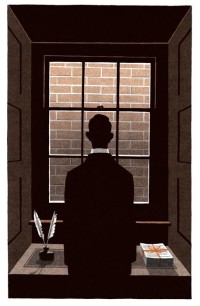

But Bartleby’s first passive-aggressive complication is that he refuses to help proofread his work. “I would prefer not to,” he says quietly, melting back into his corner. Gradually he comes to an absolute standstill, refusing not only to proofread, but to deliver letters, to leave the office, or even to copy at all. Instead, he stands staring out the window at the brick wall ten feet away.

Stranger still is his employer’s reaction. Bartleby seems to have extraordinary power over the lawyer, who is unable either to compel him to work or to have him forcibly removed. Bartleby persists like a ghost in the office until finally the lawyer finds a way to free himself of Bartleby — he thinks.

There is a whole industry of Bartleby scholarship. Is Bartleby autistic? Is he representative of Dickens, or Melville, or Christ? Is the lawyer genuinely compassionate, or a shallow, materialistic man? Is it about mental illness, sin, or economics? Is the office a mind symbol or an Eden? Should we take Bartleby’s repeated statement as tragic, or as hilarious deadpan? The tale is dense with allusion — to other stories, to Shakespeare, to the Bible, to Melville’s own life and experience and reading. What, readers have asked since it first appeared, does it mean?

I have no idea. When it comes to arguing for a determinate meaning, well… I would prefer not to. I suppose the film counterpart for this tale is Peter Sellers’ Being There, in which a man who is essentially a blank slate becomes a canvas for everyone else’s vision… but he still remains an enigma.

Yet the story always intrigues me. On this reading, what struck me was the strange hold Bartleby has on his employer. What can the most moral, caring person in the world do when captivated by the suffering of another (for there is no question that Bartleby is not all right) if the needy person won’t receive help? Bartleby’s only vocabulary is rejection and deferral. How then can he be helped to any positive action?

The other idea that always occurs to me is the suspicion that I have an inner Bartleby. (Can I comfort myself that everyone does?) Deferring preferences can be an easier default than creating a positive vision for oneself: “Not sure I want to do that… Or that… Not feeling very confident about that… Almost that, but… not quite. I would prefer not to.” How many people’s progress through life seems gentle — almost as though it is dictated more by gravitational pull than by will, or preference.

As a college student, the tale interested me intellectually. I wanted to “figure it out,” a desire available mostly because it never occurred to me that a story could be forever baffling and inconclusive. Still less would it have occurred to me that I would like a baffling, inconclusive story.

Yet I do. I enjoy returning to stories for just this reason. They, and I, grow in our relationship. My appreciation for Melville’s Bartleby is deeper now; Bartleby’s bewildering paralysis, and his employer’s ultimately unsuccessful compassion, touch my heart. “Ah, Bartleby,” the narrator laments at the end, “Ah, humanity!” On a much smaller scale than Moby Dick, Bartleby the Scrivener gives us a glimpse of the same world, one in which our human experience skates on the infinite. One need look no further than the human heart.

There is actually a Librivox recording of the entire book here. The full text of the story is also available online here.

5 Comments

Ruth

That was the class where I met you – and Steve! Great post. Wish we could hang out.

Janet

That was a momentous class in several ways, wasn’t it? You met Steve. I was captured by literary study. And I made one of my favorite friends. :-) Someday we will hang out again!

Jeane

I’ve heard of the title, but I never really knew what this book was about, before.

Barbara H.

I don’t think I have ever heard of this one. I tend not to like “baffling, inconclusive stories,” but I can see the appeal of both trying to figure it out plus thinking about it different ways at different readings. I think I have an inner Bartleby, too. I’m not sure that’s a good thing. Whatever his reasons were for “preferring not to,”mine tend to emanate from either indecision or procrastination or a soft rebellion. It wasn’t until my husband and I worked with a children’s ministry years ago that I realized there even was such a thing as soft rebellion. Usually when we think “rebellious,” we picture folded arms, stamping feet, frowns, and harsh words. But we had one little girl there then who would very sweetly refuse to do anything we asked her. Then that spilled over into other kids not wanting to do what was asked. Argh! And, funny, but I can’t remember now how we handled it. I think this usually happened at game time, and I think we eventually sent her off with someone else so she didn’t have to participate but wouldn’t drag half the other kids into not wanting to participate as well. I’m not sure why she refused – I don’t think it was because she couldn’t or felt awkward about her abilities to play (one of my own reasons for not liking game times in such settings). She had a bit of a glint in her eye while refusing, even while she spoke sweetly. Anyway – I can tend to avoid doing what I don’t want to do not by screaming and protesting but by…just not doing it.

Susan @ Reading World

Read this one a while back and I love your take on it. It was baffling but still compelling.