C.S. Lewis on “the decline of religion”

In the past I’ve reread C.S. Lewis at this time of year. Usually the essays I go back to are the ones in God in the Dock that relate to Christmas: “What Christmas Means to Me” (available online here), in which Lewis decries “the whole dreary business”; and “Xmas and Christmas: A Lost Chapter from Herodotus,” available online here.

But this year when I went back to God in the Dock, I was attracted to a different essay called “The Decline of Religion.” Lewis wrote this essay in 1946, and the attitude he is confronting seems quite familiar. Here are some excerpts.

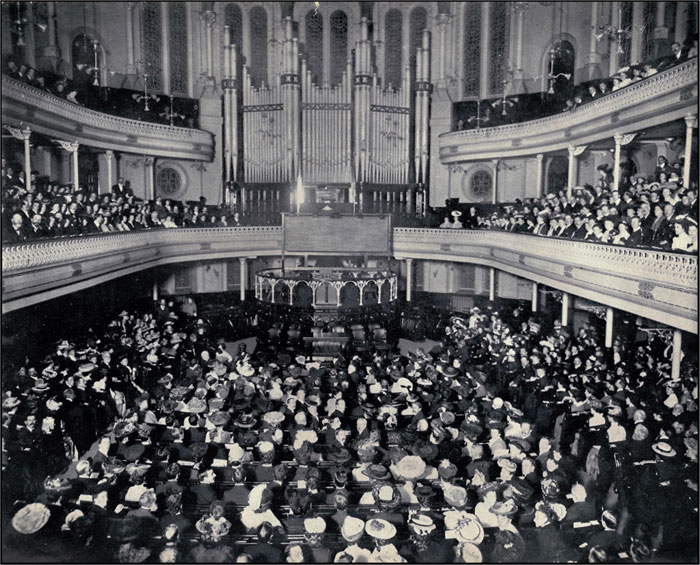

The ‘decline of religion’ so often lamented (or welcomed) is held to be shown by empty chapels. Now it is quite true that chapels which were full in 1900 are empty in 1946. But this change was not gradual. It occurred at the precise moment when chapel ceased to be compulsory… The withdrawal of compulsion did not create a new religious situation, but only revealed the situation which had long existed. And this is typical of the ‘decline in religion’ all over England.

In every class and every part of the country the visible practice of Christianity has grown very much less in the last fifty years. This is often taken to show that the nation as a whole has passed from a Christian to a secular outlook. But if we judge the nineteenth century from the books it wrote, the outlook of our grandfathers (with a very few exceptions) was quite as secular as our own. The novels of Meredith, Trollope, and Thackeray are not written either by or for men who see this world as the vestibule of eternity, who regard pride as the greatest of sins, who desire to be poor in spirit, and look for a supernatural salvation. Even more significant is the absence from Dickens’ Christmas Carol of any interest in the Incarnation. Mary, the Magi, and the Angels are replaced by ‘spirits’ of his own invention, and the animals present are not the ox and ass of the stable but the goose and turkey in the poulterer’s shop. Most striking of all is the thirty-third chapter of The Antiquary, where Lord Glenallen forgives old Elspeth for her intolerable wrong. Glenallen has been painted by Scott as a life-long penitent and ascetic, a man whose every thought has been for years fixed on the supernatural. But when he has to forgive, no motive of a Christian kind is brought into play: the battle is won by ‘the generosity of his nature’. It does not occur to Scott that his facts, his solitudes, his beads and his confessor, however useful as romantic ‘properties,’ could be effectively connected with a serious action which concerns the plot of the book.

I am anxious here not to be misunderstood. I do not mean that Scott was not a brave, generous, honourable man and a glorious writer. I mean that in his work, as in that of most of his contemporaries, only secular and natural values are taken seriously…

Thus the ‘decline of religion’ becomes a very ambiguous phenomenon. One way of putting the truth would be that the religion which has declined was not Christianity. It was a vague Theism with a strong and virile ethical code, which, far from standing over against the ‘World’, was absorbed into the whole fabric of English institutions…

The decline of ‘religion’, thus understood, seems to me in some ways a blessing.

I thought of unChristian, a book I read recently about the decline of evangelicalism that left me wondering if, as Lewis puts it, “the religion which has declined was not Christianity.”