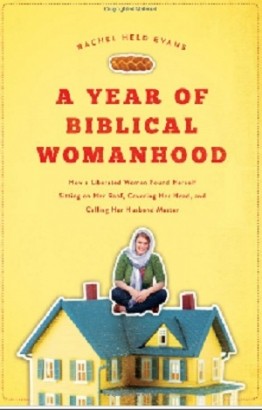

A Year of Biblical Womanhood

By now you’ll have heard about Rachel Held Evans’ A Year of Biblical Womanhood. It represents the author’s attempt to take literally every instruction to women in the Bible, in both Old and New Testaments. Focusing on a different virtue each month, she even takes descriptive statements and turns them into instructions.

By now you’ll have heard about Rachel Held Evans’ A Year of Biblical Womanhood. It represents the author’s attempt to take literally every instruction to women in the Bible, in both Old and New Testaments. Focusing on a different virtue each month, she even takes descriptive statements and turns them into instructions.

It’s a book that has garnered a lot of controversy, and I found that my reaction changed as I read, from skepticism to disappointment to, eventually, appreciation. The skepticism and disappointment were because I expected a different book. Once I was able to get my mind around Evans’ stated purpose in writing — a purpose I had to review more than once — the book became much more interesting to me.

I began expecting the book to be a study of Bible teachings — a scholarly unpacking of womanhood as depicted in the Bible. There is no justification for such an expectation, yet I seemed to have no other paradigm when I started reading. Here, though, are some excerpts from Evans’ own description of her project:

As I perhaps should have acknowledged more often and more clearly in the book, I am aware that as a Christian, I am no longer constrained by Old Testament law. But my project was an exploration of biblical womanhood—not Old Testament womanhood, not New Testament womanhood, not Jewish womanhood, not Christian womanhood….but biblical womanhood. And so part of the reason for exploring everything from Leviticus 18, to Proverbs 31, to Song of Solomon, to the epistles of Peter and Paul, was to show just how much this phrase—”biblical womanhood”—really entails, and to not take the hermeneutical devices with which Christians are so familiar for granted…

The overwhelming majority of readers seem to have understood that such exercises were meant to be hyperbolic and provocative, intended to bring some of the Bible’s most interesting word pictures to life, and to illustrate, Amelia Bedelia-style, the futility of a hyper-literal application of the text.

Her conclusions are not really earth-shattering in themselves, but I found her approach, and the debate she has sparked, to be interesting and revealing. In some respects, the book is gimmicky. Evans is certainly savvy about one aspect of evangelicalism: book publication and promotion, for she utilized all the means at her disposal to publicize her year-long project. In some of the book’s negative reviews, I can detect a note of criticism and even, perhaps, resentment about this. Evans does know how to grab the limelight, but this hardly discredits her efforts. One thing it reveals is what an eager audience she has tapped into.

It’s fascinating to me to read the negative reviews. They convince me that this is as much a book about the failure of evangelicalism to retain its hold on Evans’ generation as it is about gender. This is evident not just in Evans’ feminism, but in her refusal to play by the rules of scholarly discourse, or to take one of the predetermined positions in the gender debate. In this review, for instance, Sarah J. Flashing comes out with guns blazing before A Year of Biblical Womanhood is even published, complaining that Evans “is not faithful to biblical womanhood as taught by its adherents.” She goes on, as does Kathy Keller in this review, to delineate the book Evans should have written. Similarly, Mary Kassian writes here of her disappointment with Evans, saying, “I am keenly disappointed that Rachel based her entire book on a caricature that those at the core of the biblical womanhood movement would decry as patently false.”

“Biblical womanhood’s adherents.” “Those at the core of the biblical womanhood movement.” These are defensive responses — turf wars really. As Evans says plainly enough in the excerpts above, she is not critiquing complementarians, and her definition of “biblical” is admittedly unorthodox. But it’s also not at all prescriptive, not something she’s recommending or arguing for. Her purpose is to open up discussion, but not along the previously defined lines of debate between “complementarians” and “egalitarians”. In the process she is dealing directly with the Bible and bypassing some voices who clearly see themselves as part of its essential interpretive framework.

Are her methods legitimate? She’s not proposing a method of Bible study, and it’s a good thing. Of course there is much that she leaves out, most importantly what Kathy Keller calls the “tectonic shift” that occurs when Jesus comes. In some ways I think A Year of Biblical Womanhood has caused a good deal of confusion because it’s so easy to mistake what Evans is really up to.

But it’s a book that should be listened to. It does touch upon issues important to gender. But to me its greatest importance lies in its expression of a larger generational divide. It’s evident in a post like this one by Dan Haseltine of Jars of Clay, which is further expounded by Peter Enns here. Evangelicalism has come to stand for a rigid, highly developed perspective on what it means to be a Christian (Haseltine calls it a “massive agenda” and a “weight” on his shoulders) — a perspective younger evangelicals feel does not represent them.

Maybe evangelicalism’s way of dealing with this — through the effort to make the church a mirror of the world by appearing “relevant” in things like media, worship style, dress — has been misguided, or at least incomplete. Jesus, the Word made flesh, looked very much like everyone else did when he walked the earth. He didn’t dress in old-fashioned styles or speak archaic languages. He was “culturally relevant” to the age in which he lived.

Yet he also challenged the gatekeepers of Scriptural interpretation, in ways that angered the authorities, but inspired the multitudes to say, “He teaches with authority.” He released God’s truth from the stranglehold of habit, of legalism, of tradition. In every case he both revered God’s law and honored its spirit over its culturally-prescribed letter. He demonstrated the hermeneutics of love.

I have to say that despite having some reservations over the course of reading A Year of Biblical Womanhood, for the most part I sense in it this same yearning to release the Word from strangleholds. I sense a love for God and for his Word. I sense a longing for a fresh wind of God’s Spirit to blow through our perspective on the Bible. To these yearnings I can only say amen. I hope that the debate over this book will not stall out in jammed communication signals, but will somehow result in an enlargement of our sense of who God is and what he desires for us as men and women.

5 Comments

Ruth

You are such a great reviewer, Janet. Thank you very much for this. Now I really do want to read it — I hadn’t decided yet before I read what you wrote.

Janet

I forgot to mention it, and you’ve probably already guessed, but — it’s also very funny! I’ll look forward to hearing what you think.

Amy

Wow! Now I want to read it, and I couldn’t say that before reading your wonderfully articulated (as always!) thoughts.

Sherry

Hmmmmm. I’ve read Ms. Evans’ blog for a while, and I’m afraid that reading would color my evaluation and appreciation of her book. She doesn’t mind taking the words of those she disagrees with very literally and making them into caricatures at times. I appreciate your review, but I’m not sure if I’ll read the book or not. There may be times when I know too much about the author to evaluate the book that author writes in a fair and open way.

Janet

Yes. Your last sentence gives some great food for thought.

I’ve tried to qualify my comments here. To me the book was most interesting (and troubling) for the debate it has sparked, and the things that debate is helping me to see.