The Comstocks of Cornell

We’ve been using the Handbook of Nature Study for science this year, and I’ve grown curious about its author. I decided to read Anna Botsford Comstock’s autobiography, The Comstocks of Cornell. She had finished writing the book when she died but had not carried it through the process of publication. Because she and her husband were so highly esteemed by the Cornell community the book was edited and published posthumously in 1953, twenty-three years after her death.

We’ve been using the Handbook of Nature Study for science this year, and I’ve grown curious about its author. I decided to read Anna Botsford Comstock’s autobiography, The Comstocks of Cornell. She had finished writing the book when she died but had not carried it through the process of publication. Because she and her husband were so highly esteemed by the Cornell community the book was edited and published posthumously in 1953, twenty-three years after her death.

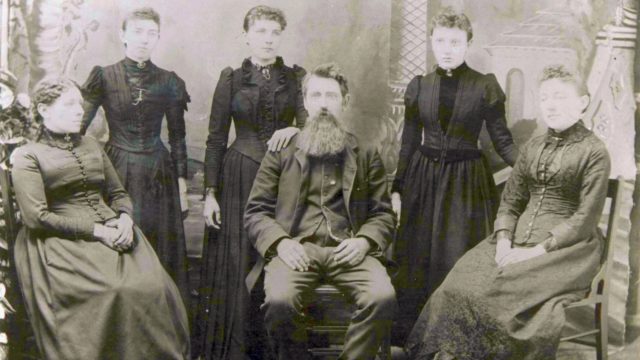

Like most autobiographies, the book is interesting both for what it includes and for what it leaves out. Included are numerous references to the institutional life of Cornell, which both Mrs. Comstock and her husband, the entomologist John Henry Comstock, were a part of almost from its inception. This account begins by tracing the two separate threads of John Henry Comstock’s childhood and Anna Botsford’s, then tells the story of their long involvement in the Cornell community where they met, married, and lived out their days. Filled with details of their various social ties, academic projects, ambitions, appointments and disappointments, this is very much a life story for public consumption.

I did enjoy learning about the childhoods of both Comstocks. John Henry faced the hardship of being passed from relative to relative for a portion of his youth before being welcomed into a generous and loving family that taught him the arts of farming and cooking. His health was not strong, but as a teenager he served as the cook on various sailing vessels on the Great Lakes during the summers to finance the education he keenly desired. He was a wonderfully determined and capable person from his difficult early years throughout his professional career, when he essentially pioneered the study of entomology at Cornell University.

By contrast, Anna Botsford’s childhood was a stable one. Her mother was a Hicksite Quaker, her father a ruggedly independent thinker, and she herself ended up a somewhat outspoken Unitarian. (Both she and John Henry faced pressure to “experience religion” as young people, pressure that resulted in both ultimately feeling alienated from Christianity.) Her parents were successful farmers, skilled in the arts of making things and providing for their needs, and Mrs. Botsford was keenly appreciative and knowledgeable about both nature and poetry. These passions found root in Anna Botsford, who eventually played an important role in the Nature Study movement established at Cornell in response to the agricultural depression of the 1890’s.

I enjoyed gleaning the many interesting facts in this narrative (though admittedly there were a number of uninteresting ones to wade through as well). Missing are a good many personal details. The description of the couples’ marriage is of a pair of colleagues who worked together in close harmony; we learn as much or more about Mrs. Comstock’s involvement in her husband’s research as we do about the nature study work that was to become her greatest contribution. But we’re left to wonder about such personal details as how the two came to an understanding that they were going to marry one another, and but for a single sentence we’re left to wonder how they handled being childless.

Part of the impersonal tone is due to the language — Anna Botsford Comstock usually refers to her husband as Mr. Comstock, for instance. And part of it is simply a stoic reserve in the narrative. Few details of painful events are included. For instance, her narrative ends without elaborating on her husband’s failing health, saying simply, “There are no words to describe his bravery and patience and cheerfulness after this calamity which, for us, ended life. All that came after was merely existence.” It’s in an afterword by a third party that we learn he suffered a series of brain hemorrhages in the last five years of his life, then outlived his wife by about seven months. Very possibly this reticence is just a further manifestation of the strength and endurance that characterized the Comstocks throughout their lives, and of their public orientation too. “Their door was always open” to those in need, and the modern sense of privacy may simply have occupied a much smaller core in their understanding of themselves.

The Comstocks of Cornell is informative as a factual account, though in some ways it only serves to increase my curiosity about this remarkable couple who left several lasting imprints on their university and the larger world.

One Comment

Amy @ Hope Is the Word

Sounds interesting!