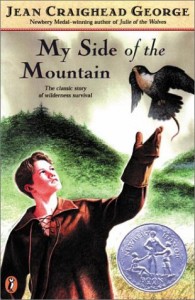

My Side of the Mountain

The girls and I finished our reading of My Side of the Mountain yesterday. It left me pondering the stark contrasts between 2012 and 1959, when Jean Craighead George’s Newberry winning classic was published.

The girls and I finished our reading of My Side of the Mountain yesterday. It left me pondering the stark contrasts between 2012 and 1959, when Jean Craighead George’s Newberry winning classic was published.

The story recounts a year in the life of Sam Gribley, a New York City boy who decides he wants to escape from his large family and the crowded city for a wilderness life. He heads to Delhi, a hamlet in the Catskills, to the family’s long-vacant farm property. There, he burns out a house in an old growth hemlock and proceeds to make do by eating roots and berries, setting snares for small animals and deer, making clothes for himself, and capturing and training a peregrine falcon named Frightful.

It interested me that his parents know where he is, but they don’t try to bring him home. In fact, his stay is not completely secret; he’s not a runaway in the ordinary sense. The Delhi librarian knows where he is, as does an old woman he meets picking berries on the hill one day. Over the course of his stay in the woods — even through a New York winter — he meets several other people, the closest of whom are his father and a vacationing English professor he names Bando, who in turn calls him Thoreau. His father and Bando actually spend Christmas with him. But they leave without the faintest suggestion of talking him out of his enterprise. On the contrary, they vow to protect him by keeping his whereabouts a mystery.

It rings strangely in my 2012 ears. But I recognize that Sam lived in a freer and safer society than ours. Even for the Gribleys, the impulse to let Sam be is ultimately thwarted by the criticism of neighbors and newspapers, and they end up joining Sam on the mountain and starting work on a house there. The interesting thing is that by the end of the story, the reinstatement of parental authority and care seems like a violation. My older daughter was indignant at the idea of a house being built on the mountain where Sam has worked so hard to live off the land.

The confusion of feelings by the time we get to that part of the story is striking. By the end of winter Sam has gradually become lonely on the mountain, and he actually welcomes visitors. It’s something he can’t quite work out in his mind — the conflict between the desire for human company, and the desire to be self-sufficient. He’s delighted to see his family, and this feels right to us as readers. Yet somehow the signals jam when they start to build the house because we want to see his independence respected too. In some important ways, he has grown up. George seems to be exploring what society does to personal freedom, a theme she puts into Bando’s mouth when he comes to visit Sam in the spring:

Let’s face it, Thoreau; you can’t live in America today and be quietly different. If you’re going to be different, you’re going to stand out, and people are going to hear about you; and in your case, if they hear about you, they will remove you to the city or move to you and you won’t be different anymore.

It’s a bittersweet, prophetic observation.

The action of the novel is absorbing, but I was equally interested in the persistent theme of Sam’s reading and writing habits. Most of his knowledge of the woods is accumulated from books before he ever arrives on the mountain, and to ensure that more knowledge will be available when he needs it, the first place he goes to in Delhi is the library. He’s a very purposeful reader with an excellent retentive mind. In addition, he is a faithful writer who keeps notes and sketches in his journal. My older daughter was reading Dipper of Copper Creek, another J.C. George book, simultaneously with our reading aloud of this book, and when I asked her what she thought of it she was tentative. “It’s not like it’s an interesting nature journal, like My Side of the Mountain, that has ideas I can use outside,” she explained. There seems to be something compelling about a first-person journal account, something less crafted and more immediate — and perhaps more true to lived experience.

This brought to mind a host of other nature writers who seem to find the journal form fitting to chronicle their experiences with nature: Thoreau, John Muir, Mary Austin, John Burroughs, Aldo Leopold, Sue Hubbell, to name a few. Among child characters, the one who comes to mind immediately is Sam Beaver of Trumpet of the Swan, who notes his observations in a diary and concludes each day’s entry with a question to ponder as he falls asleep. “Why does a fox bark?” he wonders. “How do birds know how to build their nests?” It seems like a common impulse to record our experiences with nature, partly perhaps because it mirrors our own inner complexity, but mostly because nature is inexhaustibly interesting.

2 Comments

DebD

oh wow. It’s been a few years since I read that aloud to anyone. But, boy that quote sure is prophetic.

Barbara H.

This a title I’ve seen over the years and thought I ought to read some time but just never picked up. Same with the film.

It would be very hard as a parent to let a child go off in the wilderness and live alone. These days there would probably even be charges of child neglect. I read more about the book on Wikipedia, and I like that he wrestles with wanting to be alone but needing companionship. I wrestle with that myself.