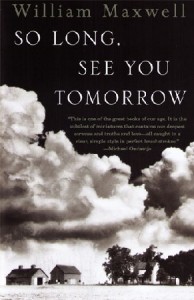

So Long, See You Tomorrow

I finished this book last night, turned off the light, and lay numbly in bed for a few minutes. “What a depressing book,” I muttered.

I finished this book last night, turned off the light, and lay numbly in bed for a few minutes. “What a depressing book,” I muttered.

“Why did you read it then?” asked my husband (who I thought was already asleep).

It is, above all, heartbreaking. Yet it’s also perfectly crafted — truthful, spare, lyrical, ruthless in the way it tells its story, deeply compassionate in trying at all. I guess it’s a book that reveals what a mysterious thing literary judgment is.

So Long, See You Tomorrow is classed as fiction, but nearly the first half is the narrator sharing his memories of childhood in Lincoln, Illinois. Some of this must be Maxwell’s memoir, but not set forth purporting to be documentary fact. As all writers of autobiography know, none of us is able to write such an autobiography even if we try because the caprices of memory render our own past at least partly fictional to us. This is one of the novel’s themes — the unreliability of memory.

Yet this narrator is trying to recover a truth from his own past, and trying as well to redeem a single awkward moment that has stuck with him for decades: the day he passed Cletus Smith, a friend from Lincoln, in the halls of a Chicago high school, and didn’t acknowledge him. The two had played in the scaffolding of the narrator’s house while it was being built for a brief season, but when Cletus’s father shoots his next door neighbor and then killed himself, the two boys never see one another again until they end up in the halls of the same large high school years later. Maxwell seems to offer art as a form of restitution for his own adolescent awkwardness and failure to know what to say, and for what he fears was its effect — indifference toward, or worse, judgment on, Cletus, whose suffering must have been unthinkable.

But here, the narrator seeks to make amends by making himself think about it. He establishes a frame of reference by telling about his own childhood in Lincoln, remarking, “Very few families escape disasters of one kind or another, but in the years between 1909 and 1919 my mother’s family had more than its share of them.” One of these disasters was the death of his mother in the 1918 influenza epidemic. Though his father remarries, and though his family is comfortably middle class, there is an atmosphere of emotional chill and loneliness in the home that leaves its mark on the young boy. It’s when the family’s new home is being built that he meets Cletus, who appears one day at the construction site and the two play with an easy companionship that seems to salve both boys’ wounds.

It turns out that Cletus is in town because his family has been shattered by an affair between his mother and the neighbor, a tenant farmer on land adjoining that of the farm Cletus’s father works. The two had been best friends, and the betrayal resulted in scandal and, ultimately, tragedy. When Cletus leaves the construction site one day with his usual farewell — “So long, see you tomorrow” — it turns out to be the day his father’s body is found, and his mother takes the children away from Lincoln for good.

The last two thirds of the book consist of Maxwell’s attempt to imagine Cletus’s family history. Having missed his opportunity to show compassion in the single chance meeting the boys have as teenagers in a hallway in Chicago, this narrator pays homage to Cletus by stepping into his shoes in the only way a writer knows how, through the empathetic imagination of the artist. Nowhere does he lapse into nostalgia or sentimentality or melodrama. His descriptions evoke the time, the landscape, and the personal dynamics between people with a discerning eye and a masterly attention to detail.

There is much more that could be said about Maxwell and about this slim novel, but I would rather leave it to be discovered. It breaks the heart. I can’t pretend it doesn’t. But I think that probably John Updike is right when he says, “Maxwell’s voice is one of the wisest in American fiction; it is, as well, one of the kindest.”

3 Comments

Amy @ Hope Is the Word

This sounds intriguing, but the heartbreaking part turns me away. I have never even heard of this author!

Janet

He’s new to me too. He was an editor for the New Yorker for years, and he helped a lot of writers get established — Updike, Welty, others. But he was also a distinguished author himself.

I know what you mean about turning away from sad stories!

DebD

wow, what a fascinating idea. There’s probably not many of us who don’t have something we regret from our teen years. I’m not sure I’d want to go back there and relive it in my mind though. I think regret is one of the worst types of sadness so I’m not sure I would want to read this book.