The Prodigal God (and golden eggs)

Timothy Keller’s Prodigal God is a short book in which Keller uses the parable of the prodigal son as a framework for discussing two different types of lost souls: the profligate (the younger brother of the parable) and the legalist (elder brother). The former rebels by breaking all the rules, the latter by keeping them. Both need Christ’s salvation, but for Keller it seems the elder brother is in a more precarious place spiritually because his sin may not be apparent to him.

Timothy Keller’s Prodigal God is a short book in which Keller uses the parable of the prodigal son as a framework for discussing two different types of lost souls: the profligate (the younger brother of the parable) and the legalist (elder brother). The former rebels by breaking all the rules, the latter by keeping them. Both need Christ’s salvation, but for Keller it seems the elder brother is in a more precarious place spiritually because his sin may not be apparent to him.

Since there are plenty of thorough reviews out there, I’m not going to add much to the din. I found the book to be an interesting discussion of two spiritual “types,” though I didn’t find it novel to regard the parable as being about both brothers. I read somewhere that Keller wrote the book in an attempt to open dialogue between the churched and the unchurched, and perhaps it does this. It struck me as addressed primarily to believers, though, with its emphasis on the elder brother’s legalism.

I’m not sure I’d call it a book “about” the parable, though. The story Jesus told seems to be used here as a mere jumping-off point for a discussion about something else Keller wants to say, and I’m wary about this way of treating Scripture. Not long ago, I heard another altogether different exposition of the “real meaning” of this story as being about the economy of the Kingdom of God. This is a parable, a simple story Jesus told to convey truth to a diverse audience. Reading so much into it seems like overkill, more likely to carry us away from the “heart of the Christian faith” than to bring us home. Sometimes when you look too hard at something, you stop seeing it.

I hasten to admit that I’m not sure I understand Jesus’ reasons for using parables. It has something to do with hiding and revealing at the same time — something for which the story form is well-suited. Here’s how he explains it in Matthew 13:

13This is why I speak to them in parables:

“Though seeing, they do not see;

though hearing, they do not hear or understand. 14In them is fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah:

” ‘You will be ever hearing but never understanding;

you will be ever seeing but never perceiving.

15For this people’s heart has become calloused;

they hardly hear with their ears,

and they have closed their eyes.

Otherwise they might see with their eyes,

hear with their ears,

understand with their hearts

and turn, and I would heal them.’ 16But blessed are your eyes because they see, and your ears because they hear.

Stories are powerful because they cannot be fully “explained.” I find that the ones that stick with me most are the ones I don’t fully understand, but that seem to point toward a truth I need. They come clear as they haunt me through time and experience. In a sense they achieve their power in the peripheral vision; their meaning becomes most apparent when I’m looking at something else.

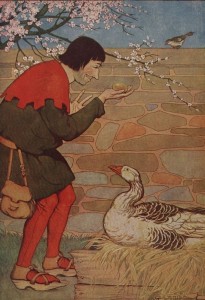

I’m not sure what the implications are for “teaching” the stories of Scripture, except to underscore the importance of reading them prayerfully and attentively. The few times Jesus explains a parable to his puzzled disciples (here or here, for instance), he offers a fairly straightforward meaning. Certainly his explanation is brief. It seems clear that pulling them apart strand by strand and reconstructing them in a way that leaves no ambiguity isn’t really the answer. That’s kind of like killing the goose that lays the golden egg to get at the secret — and finding that you’ve destroyed the source of your riches.

I’m not sure what the implications are for “teaching” the stories of Scripture, except to underscore the importance of reading them prayerfully and attentively. The few times Jesus explains a parable to his puzzled disciples (here or here, for instance), he offers a fairly straightforward meaning. Certainly his explanation is brief. It seems clear that pulling them apart strand by strand and reconstructing them in a way that leaves no ambiguity isn’t really the answer. That’s kind of like killing the goose that lays the golden egg to get at the secret — and finding that you’ve destroyed the source of your riches.

Jesus’ parables were meant not just for the experts, but for all seeking listeners. One of the ways we can guard the great gift and privilege of that is by staying in touch with the stories themselves, and having faith in their Teller to speak directly through them what we most need to hear. For me, that means acknowledging the great appeal of the Father’s generosity and grace, and accepting the invitation to emulate Him. He’s the real hero of the story. He’s the one who wins my heart.