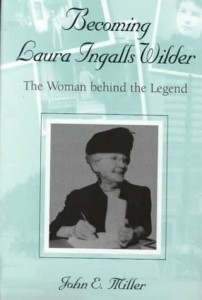

Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder

I read Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Woman Behind the Legend for the first time in the fall of 2007. My daughters and I had been exploring the earlier Little House books for the first time since I’d experienced them as a child, and I had a desire to learn more about the author behind these wonderful stories. Now we’re into the later books in the series, and my interest was piqued again. Why the same biography? Because it left me feeling deflated the first time, and I wanted to give it another chance.

I read Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Woman Behind the Legend for the first time in the fall of 2007. My daughters and I had been exploring the earlier Little House books for the first time since I’d experienced them as a child, and I had a desire to learn more about the author behind these wonderful stories. Now we’re into the later books in the series, and my interest was piqued again. Why the same biography? Because it left me feeling deflated the first time, and I wanted to give it another chance.

Some of the reviews over at Amazon fault this book for being “too scholarly.” I don’t feel that way at all. I love the wealth of detail John E. Miller supplies about the world that surrounds the fictional world of the Ingalls family. Reading the stories, we have a strong sense of one very tightly-knit family facing the elements and living the great adventure (or the great version of the adventure) of American independence and resourcefulness against the backdrop of westward expansion. Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder provides a broader, more documentary, fascinating lens for experiencing the Ingalls family story.

The books leave me with a sense of warmly loving security. This biography reminds me that Laura’s life was more than anything else a tale of extreme and unrelenting poverty, and little of the material success usually associated with “the American dream.” The homespun contentment of the Little House books is expanded here into a more complex fabric of accompanying heartache and failure and courage made more admirable through this unromanticized reflection on the details of the life that began as Laura Ingalls, became Mrs. A.J. Wilder, and ended up “becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder” the beloved children’s writer.

As I read, I had many opportunities to speculate on a subject that’s long interested me: how life is written into autobiography. The Little House books are fictionalized autobiography, but Laura at one point asserted that every event was accurate. This isn’t true; names and characters were changed, events were reordered for the sake of narrative structure, and much is left out, pointing to the mysteriousness of how we create ourselves in our own life story. Why do we include some things and not others? How reliable is our memory? And to what extent is the result, if not accurate, “truthful”?

But more interesting (and sometimes sad) than this kind of abstract rumination are the facts of a long life, well-lived. Almanzo emerges from these pages as a largely silent man, very different from the genial and expansive personality Laura’s father exhibits in the stories — able and hard-working despite physical weakness, but not merry or especially striking. Laura is depicted as a cheerful, ambitious, sometimes manipulative person, in some ways the stronger party in the marriage. And their daughter Rose Wilder Lane is prominently featured as an extremely intelligent and gifted person who never seemed to manage to find her own identity. In these pages she appears to be a tangle of love and generosity mixed with resentment and a strong desire to dominate and control.

Miller uses Rose’s letters and diaries to reconstruct some of the tension that existed between mother and daughter. He takes a balanced view of the controversy over Rose’s role in the authorship of the books. I come away with the sense that Laura’s was the lived life, hers the descriptive eye and the interpretation of her experience, whereas Rose was the editor — an editor given quite a free hand, but not on an equal footing with her mother by any means in the creation of the stories. She and Laura discussed their revision and editing at great length, and it was Laura who retained the authorial decision-making power.

When it comes to questions of personalities or the subtleties of family relationships, I’m not sure how reliable Miller’s inferences are. When all is said and done, Laura and Almanzo’s life together retained a veil of privacy that prevents anyone from truly knowing what their relationship was like. And Rose’s copious diaries and letters betray a rollercoaster of feelings about her relationship with her mother of which there’s no evidence Laura was even aware, and about which the lack of any comparable personal revelation on her side makes it impossible to judge. For the most part, Miller handles this inconclusiveness with delicacy.

There’s no question that Laura Ingalls Wilder was determined, capable, keenly observant, devoted, faithful to her Christian profession, and a skilled and knowledgable farm wife who exhibited an equal partnership with her husband advanced for her time. On top of all of this, at age 44 she began to write, and in her sixties emerged as a talented author whose books are truly unique as lived history. She lived consistently with her ideal, as she expressed it: “Love and service, with a belief in the future and expectation of better things in the tomorrow of the world, is a good working philosophy.”