War and Peace

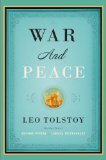

This novel spans roughly 15 years, from 1805-1820, centering on Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 and Russia’s resistance. More than 500 characters populate its pages, all of them well developed, and several of whose stories are told in great detail. Every social class from peasant to emperor is represented, and every stage of maturity is touched upon.

This novel spans roughly 15 years, from 1805-1820, centering on Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 and Russia’s resistance. More than 500 characters populate its pages, all of them well developed, and several of whose stories are told in great detail. Every social class from peasant to emperor is represented, and every stage of maturity is touched upon.

It’s an amazing book.

There were two aspects that made the greatest impression on me. One is Tolstoy’s sympathetic imagination. The way he renders these characters shows an incredible degree of both keen observation and wisdom. Their personalities are so distinct and so diverse, and Tolstoy develops them so completely, that I’ll never forget some of them. Sometimes he’s exact and loving, as with Pierre and Natasha and Prince Andrei and Princess Marya. Other times he’s exact and merciless, as with Countess Bezhukov. Always, he’s convincing.

The second aspect of the book that stood out to me was its theory of knowledge. (That sounds pretty dry, but it doesn’t come across that way in the story!) Everyone in this tale is trying to impose some sort of order on experience. For Princess Marya, it’s religion. For Nikolai Rostov, it’s military life. For Pierre, at least for awhile, it’s freemasonry. For Countess Bezhukov and Boris Drubetskoy, it’s social status. For Prince Andrei, it’s reason. None of these are shown to be effective at making life meaningful. Ultimately, I thought Tolstoy’s heroine was Natasha Rostov, who approaches life intuitively and passionately, instead of getting weighed down by analysis. She’s not haunted, as the other characters are, by questions about why things are the way they are. She operates more by compassionate instinct than by rational thought, and she’s far and away the most appealing and vibrant character in the book. Pierre is a close second, a kindred spirit to Natasha who arrives at the same approach himself and makes a fit companion for her.

All of the characters seem to have some mystical experience at one point or another when they recognize that human life is ultimately inscrutable. This moment when Prince Andrei thinks he’s about to die on the battlefield is representative of what I mean:

There was nothing over him now except the sky — the lofty sky, not clear, but still immeasurably lofty, with gray clouds slowly creeping across it. “How quiet, calm, and solemn, not like when we were running, shouting, and fighting; not at all like when the Frenchman and the artillerist, with angry and frightened faces, were pulling at the swab — it’s quite different the way the clouds creep across this lofty, infinite sky. How is it I haven’t seen this lofty sky before? And how happy I am that I’ve finally come to know it. Yes! everything is empty, everything is a deception, except this infinite sky. There is nothing, nothing except that. But there is not even that, there is nothing except silence, tranquillity. And thank God!…

There’s no question that Prince Andrei is seeing something significant here, and it has to do with getting a glimpse beyond the chaos of human activity into something that can only be expressed in terms of the feeling of peace he has when he contemplates the sky.

One of Tolstoy’s main agendas in this novel is to make a similar point about the way historians try to make meaning out of human events. Why do things happen the way they do? Why is one battle lost and another won? Why do the fates of nations play out the way they do? Often, Tolstoy’s narrator expounds on how the methods historians use are inadequate. In the same way Prince Andrei recognizes in the sky something larger than his style of accounting has been able to measure, Tolstoy sees in human life forces that historians fail to take into account when they see history in a linear fashion, or as the result of a few men’s decisions: “the spirit of the people,” “necessity,” and other nonrational things are every bit as powerful as the will of emperors or political processes — often moreso. On the whole Tolstoy puts little stock in scientific knowledge of the kind that ascribes motives and causes. (At one point he defines science as “an imaginary knowledge of the perfect truth.”)

For someone who wants to depict the sprawling complexity of human experience, this novel with its epic scope and ever-instructive narrator is the perfect artistic vehicle. It’s a masterpiece, one impossible to close without many different thoughts and impressions. Far be it from me to commit Tolstoy’s cardinal sin by reducing it to dry analysis! I do however plan to debrief with a viewing of the classic 50’s movie version with Audrey Hepburn as Natasha and Henry Fonda as Pierre. A bowl of popcorn and a more passive experience of based on this grand tale should make a suitable bookend to an exhausting but satisfying read.