Art Lesson

I’m really enjoying Madeleine L’Engle’s The Irrational Season, and trying not to read it too quickly. Today I read her commentary on some works of art.

L’Engle writes, “Christian graphic art has often tended to make my affirmation of Jesus Christ as Lord almost impossible, for far too often he is depicted as a tubercular goy, effeminate and self-pitying.” (She doesn’t mince words, does she?) But she goes on to describe a visit to the Church of the Chora in Istanbul that excited her because its art offered an alternative. It made me curious.

Here’s the Church of the Chora. It was converted into a mosque in the 16th century by the Ottoman rulers (about whom we’re learning in history right now), but it’s been a museum since 1948:

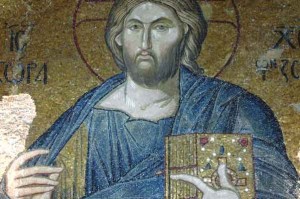

She describes her experience of stepping over the threshold and being immediately confronted by

a slightly more than life-size mosaic of the head of Christ, looking at us with a gaze of indescribable power. It was a fierce face, nothing weak about it, and I knew that if this man had turned such a look on me and told me to take up my bed and walk, I would not have dared not to obey. And whatever he told me to do, I would have been able to do.

But the scene she’d gone expressly to see was the fresco over the altar. Here’s her commentary:

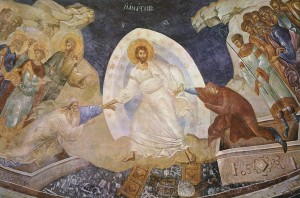

I stood there, trembling with joy, as I looked at this magnificent painting of the harrowing of hell. In the center is the figure of Jesus striding through hell, a figure of immense virility and power. With one strong hand he is grasping Adam, with the other, Eve, and wresting them out of the power of hell. The gates to hell, which he has trampled down and destroyed forever, are in cross form, the same cross on which he died.

I don’t know much about iconic art (right term?), and as a lifelong Protestant I don’t have any experience of the role it plays in worship. But I can imagine that sitting among ancient pictures like these regularly must be a powerful experience.

First, they’re ancient… They give a true sense of antiquity, of the generations that have lived and worshiped before. This church was built originally in the early 5th century, rebuilt around 1080, then modified for the last time two centuries later. The artwork inside (there’s plenty more) was created between 1315 and 1321.

Second, the painstaking work involved in the creation of works like this testifies to the great worthiness of their subjects. Frescos are made by painting on wet plaster, mosaics by affixing tiny fragments of stone or glass. To create the kind of detail in these pictures, their artists worked long and patiently, guided by a vision of the final product that only they could see.

Last, these pictures have an effect similar to hymns. Both forms involve packing a great deal of theology into a fairly rigid, condensed form. Accordingly, they pack a punch! They remind me of Daniel’s dreams in the Bible, or some of the prophetic visions, in which layers of meaning speak from a single visual idea. I feel thankful for this book that raised my curiosity.