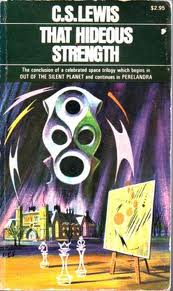

That Hideous Strength

The Hideous Strength holds all this Earth in its fist to squeeze as it wishes. But for their one mistake, there would be no hope left. If of their own evil will they had not broken the frontier and let in the celestial Powers, this would be their moment of victory. Their own strength has betrayed them. They have pulled down Deep Heaven on their heads. Therefore, they will die. (Ransom to Merlin, That Hideous Strength)

It’s a morality tale about the dangers of unchecked ambition, a modern day Tower of Babel, a warning that totalitarianism can take many forms, and a melding of science fiction with theosophy the success or failure of which I’m still mulling. This third and final book in C.S. Lewis’s space fantasy series left George Orwell feeling cheated. “Unfortunately, the supernatural keeps breaking in, and it does so in rather confusing, undisciplined ways,” writes Orwell. “[Lewis] is entitled to his beliefs, but they weaken his story, not only because they offend the average reader’s sense of probability but because in effect they decide the issue in advance.” Much though I love Lewis, and much though I share his beliefs, and much though I found this to be enlightening reading in many respects, I’m inclined to agree that the eruption of theology/the miraculous into this novel seems to interrupt the story. Rather than a seamless whole, this book had more the quality of patchwork.

It’s a morality tale about the dangers of unchecked ambition, a modern day Tower of Babel, a warning that totalitarianism can take many forms, and a melding of science fiction with theosophy the success or failure of which I’m still mulling. This third and final book in C.S. Lewis’s space fantasy series left George Orwell feeling cheated. “Unfortunately, the supernatural keeps breaking in, and it does so in rather confusing, undisciplined ways,” writes Orwell. “[Lewis] is entitled to his beliefs, but they weaken his story, not only because they offend the average reader’s sense of probability but because in effect they decide the issue in advance.” Much though I love Lewis, and much though I share his beliefs, and much though I found this to be enlightening reading in many respects, I’m inclined to agree that the eruption of theology/the miraculous into this novel seems to interrupt the story. Rather than a seamless whole, this book had more the quality of patchwork.

And so I’m reminded how capricious my tastes really are. Maybe it’s not great literature, but — I really liked it. This is not the first time I’ve read it, but I felt I grasped more this time, and it made me work.

The basic situation: in the heart of England, the N.I.C.E. (National Institute for Controlled Experiments) is prosecuting a campaign for the improvement of humanity. On the surface they use the lingo of social engineering and progressivism, but in reality the guiding powers are spiritual — dark beings called macrobes whose goal is to dominate and destroy humanity. “One must guard against the error of supposing that the political and economic dominance of England by the NICE is more than a subordinate object,” points out Professor Frost. “It is individuals that we are really concerned with.” I was reminded of Screwtape with his campaign to consume individual souls when Wither, the NICE’s deputy director, comments, “I would welcome an interpenetration of personalities so close, so irrevocable, that it almosts transcends individuality. You need not doubt that I would open my arms to receive — to absorb — to assimilate this young man.” He speaks of Mark Studdock, a young fellow of a small English college whose involvement with the NICE fulfills a lifelong obsession to belong to the “right” group, but whose personal development makes for much of the drama of the story.

His wife Jane is the other main character. As the N.I.C.E.’s program advances, Mark and Jane find themselves on opposite sides politically and spiritually. Jane resides with Ransom, the hero of the two preceding books in the trilogy, and a small assortment of other ordinary English folk who belong to the ancient civilization of Logres — Lewis’s representation of mythic England, the England of Arthurian legends and noble possibilities, existing in continual tension against actual fallen England. The planetary oyarsa (or angels) that come to earth’s rescue from the macrobes (or demons) uphold the possibilities of Logres.

The redemption the novel describes includes several strands. There is the redemption of individual choice — the soul — against the totalitarian logic of the institution. There’s the throwing off of technocracy, which the N.I.C.E. seeks to elevate as a god, and the restoration of theocracy. There’s the restoration of a link between humanity and nature, a salvation from the alienating effects of the machine. (Ransom and company grow a thriving vegetable garden and keep a pet bear, for instance. Also Merlin the magician comes back to life to help their cause, restoring commerce with certain lesser “spirits,” depicted as shadow-versions of the planetary beings, who animate earthly nature. These, the narrative suggests, are what ancient mythologies perceived as gods… and they return to life as part of earth’s triumph. I thought of both Miracles and The Problem of Pain as I read Lewis’s vision here of a Nature restored to unity.) And there’s the rescue of human sexuality — the masculine and the feminine — from both the scientific viewpoint that would dissect and separate, and from the deliberate program of the macrobes to “reverse all natural repugnances,” devouring and destroying humanity.

Above all there’s the restoration of right speech. Christ in the scripture is depicted as “the Word,” and in these stories it’s fitting that Ransom, mediating between celestial beings and earthly ones, is a philologist. One of the dominant instruments of the N.I.C.E. is institutional vagueness of language, and domination of the Press. When the institute falls, it falls in a breakdown of language at a banquet where speech becomes gibberish and chaos reigns supreme.

This book appeared in 1943, but there’s much that seems to speak to the trends of 2008. Whether or not its readers agree with Lewis’s beliefs, this book is sure to challenge them with its shrewdness about human nature and human institutions, and its wicked sense of humor. It’s well worth reading — and rereading.