Revisiting ‘Wise Blood’

My task, which I am trying to achieve, is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel — it is, before all, to make you see. That — and no more, and it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there, according to your deserts, encouragement, consolation, fear, charm, all you demand — and, perhaps, also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask.

–Joseph Conrad, in whose terms Flannery O’Connor defines her own literary aims

My book group chose Flannery O’Connor’s novella Wise Blood for our second read. I read it 20 years ago, and I’ve really enjoyed revisiting it, Gothic and grotesque trappings notwithstanding. I remembered bits and pieces here and there, but most of it felt like I was reading it for the first time.

My copy includes three of O’Connor’s stories, but I surfed the web and found a couple of other interesting covers. Here’s one that picks up on the tale’s preoccupation with eyes and seeing:

And here’s one that features a scrupulously protected — and punished – heart:

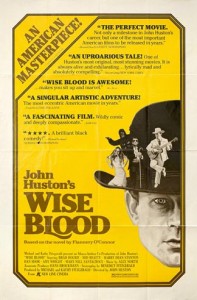

The cover of John Huston’s 1979 film version depicts the key characters dancing on the brim of protagonist Hazel Motes’ preacherly hat:

All of them evoke different aspects of a story rich with meaning. Some observations:

Eyes and seeing: the protagonist is Hazel (as in hazey) Motes (“Cast out the mote in your own eye before worrying about the plank in someone else’s”). Various characters comment on his stare, which seems focused on the inward or the hidden. Asa Hawks, an alcoholic sham preacher “hawking” religion, poses as a blind man after trying unsuccessfully to put his eyes out as proof of his faith. Haze follows suit, and blinds himself. It evokes the biblical references to seeing — the eyes of the blind being opened, the kingdom of Heaven being unexpected and visible only to “fools” and “children,” seeing through a glass darkly…

Birds and hunting. Sabbath Hawks preys on Haze Motes under sky with a bird-shaped cloud; they visit a gas station showcasing a bestial version of themselves: a one-eyed bear caged with a chicken hawk. (I love the scene where Sabbath comes out from behind the tree and Haze runs away — she literalizes the ”ragged Jesus moving from tree to tree in his mind.”) Enoch Emory has a washstand modelled after a bird of prey, and it becomes the tabernacle for the new idol/spiritual cleanser.

Rituals. These secular characters are more “religious” than most people of faith that I know. Haze, a young serviceman returning to his southern home to find his family gone, is set against his inherited faith. He’s kept his mother’s Bible like an anchor at the bottom of his suitcase, and used her glasses to read it (eyes again); he has a hard time getting away from his second generation faith. Even his attempts at sinning have the joyless quality of empty religious rituals perfunctorily performed. Same with Enoch Emory, a skinny voyeur who has certain rituals he has to go through. All of the characters (except maybe Haze) fall back on stock phrases they clearly don’t mean. (Hoover Shoates, Enoch, and Sabbath all speak feelingly in Jesus cliches, for instance.)

Orphans: Haze’s family is gone. Enoch is abandoned. Sabbath is illegitimate and her father wants to get rid of her. Haze’s landlady is a widow. The only fathers mentioned are derelicts (Asa Hawks), criminals (Enoch Emory’s father), or hypocrites (Haze’s father).

Blood: Not just Haze, but Enoch, feel they have “wise blood” — an intuition that guides them better than than any traditional wisdom, and that bypasses reason. It’s interesting… Our style of Christianity doesn’t emphasize (i.e. talk much about) blood, but Jesus certainly did, as did the atonement, as did the Old Testament with its insistence on certain kinds of dietary restrictions and sacrifices because “the life of a creature is in its blood.” Is it safe to locate some of the deepest mysteries of the Christian faith in the blood? Yet it’s easy to keep at the edges till a strange little book like this moves it to the center.

Religious motifs. Haze has an injured heart, with a piece of shrapnel still lodged there, suggestive of original sin. The cabinet in Enoch’s washstand is “tabernacle-like.” The “mvsevm” is church-like, complete with a (mock) unsayable name (like YHWH?) and the mummy is kept in a kind of inner holy-of-holies. My college English teacher pointed out that when Sabbath cradles it as a child, it mimics/parodies one of those vignettes of the Madonna and child that can be set up in a person’s yard. (This is about all I remember from my first reading of Wise Blood.) Onny Jay Holy calls Haze “a prophet.” And there’s the car, a correlative for Haze’s life. (“Get your head out of my car, Holy,” he says at one point.) He insists it will “get him anywhere he wants to go.” When it goes, so does his rebellious self.

A keen ear for dialect, an astute observing eye, and perfect comic timing. Too many examples to choose from here…

The best names ever. Hazel Motes. Sabbath Hawks. Mary Brittle. Onny Jay Holy…

Writing that can’t resist poetic phrases, even when they’re put into implausible mouths. For instance, Enoch Emory describes a woman whose hair “looked like ham gravy trickling over her skull.” Sabbath accuses Haze of tearing up her tract and “sprinkling it all over the ground like salt.”

Questions:

- What’s gained by using this weird genre? It highlights some commentary on southern culture, and southern evangelical culture (circa 1952, and forward-looking in its insight into the collision between consumerism and faith). It has the surreal quality of a dream, where true things on the periphery appear in their full potency by being placed in a different setting. And in a way, a book like this disarms the reader. It’s so exaggerated and bizarre that the piercing insights catch you off guard.

- What’s this story “about”? I guess I’d call this book a kind of spiritual quest. In the intro, Flannery O’Connor says she thinks Haze has integrity because he can’t escape the “ragged Jesus moving from tree to tree in the back of his mind.” He wants the truth – not money; not sensual pleasure; not human companionship. I think I would agree that Haze is a philosopher of integrity – and a superb characterization of a prickly, morose prophet. I think I like the first cover best (above) because it captures the quest to see invisible realities.

- Why does Enoch hate animals so much? What do we make of his storyline?

- What’s Haze busy doing on the front porch — when he’s “too busy” to preach?

- What’s the landlady looking for in Haze?

- Is there anyone genuinely saved and purposeful in this story? Or is everybody selling something? (Hoover Shoates, Sabbath, the landlady, Enoch…)

- What prompts Haze to blind himself – what happens to his car, or what he’s just done with it?

- What does the blinding accomplish for him?

- If Haze finds a kind of peace or salvation at the end, what’s with the barbed wire and rocks in his shoes?

- Is this a hopeful story, or all dark? And if it’s all dark, what’s the point?