To Stay Alive: Pondering War

I’ve gotten a little off track in this blog lately. When I started blogging, it was partly to wrestle with things — books, ideas, life. The “books” category has turned into me writing a review of everything I read. Nothing wrong with that, except that it becomes kind of formulaic.

I’ve gotten a little off track in this blog lately. When I started blogging, it was partly to wrestle with things — books, ideas, life. The “books” category has turned into me writing a review of everything I read. Nothing wrong with that, except that it becomes kind of formulaic.

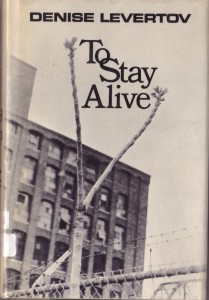

This book doesn’t really permit a formulaic approach. So this won’t be a “review” so much as a long and winding passage through my own confusion. For starters, my reading it is an accident; I was under the impression that it was an autobiography when I requested it through interlibrary loan, but in fact it’s a volume of activist poems, letters, and journals written during the Vietnam War. (Don’t ask me how I missed that boat!) For finishers, it’s a subject that leaves me conflicted — not the Vietnam War, but war in general.

Of course I hate war. Clint Eastwood’s recent film Flags of Our Fathers made the point for me again: it’s a foul business, foul on all sides. In the Bible, some of the hardest passages to stomach are where Israel slaughters other nations in conflicts that seem to show God siding with some humans against other humans — some created beings made in his image, against other created beings made in his image. And of course we’re at war right now, a war that’s having problems, and that I feel cynically hopeless of ever having adequate perspective to truly judge.

On the one hand, I want to support the troops. They are defending our country, the ideals of which I hold dear, and in which I hope my children will live out their days safely. I recognize that some great advances have occurred right here in our own nation that would never have been achieved without war. “Some things are worth fighting for” makes sense to me.

But on the other hand: the cost in lives, the moral rationalizations, the brutalization of both participants and observers, the systemic greed, the institutionalized language custom-made for indirection.

Hindsight shows the morass the Vietnam War became. Denise Levertov, who writes that this book is “a record of one person’s inner/outer experience in America during the ’60′s and the beginning of the ’70′s,” was married during this period to Mitchell Goodman, tried as a co-defendent in the problematic Spock trial for helping men elude the draft. There are undercurrents of the confusion, glimpses of the violence and grief. But there’s also a strong sense of the conviction Levertov and the others felt about the worthiness and effectualness of their activism. There were a lot of these poems that I didn’t feel I really “cracked open.” They kind of went by me.

But a few are unforgettable. They make it hard for me to sit comfortably here on the fence, hating carnage, hating the way we’re entangled with the systems and lifestyles that feed war, hating the powerlessness of being unable to choose a warless world or believe I can make this into one — yet appreciating, fiercely, the bravery of men who defend me and my children, who make us articulate our ideals. I find it hard to speak out against war without feeling like I’m pulling the rug out from under them.

Take this one, for example. It begins,

You who go out on schedule

to kill, do you know

there are eyes that watch you,

eyes whose lids you burned off…

Others are thought-provoking in ways that reach beyond their immediate context:

Robert reminds me revolution

implies the circular: an exchange

of position, the high

brought low, the low

ascending, a revolving,

an endless rolling of the wheel. The wrong word.

We use the wrong word. A new life

isn’t the old life in reverse, negative of the same photo.

But it’s the only

word we have…

Berry’s essay “In Distrust of Movements” captures some of the feelings I have. He too speaks of this circular quality of movements, that leads them eventually to turn on themselves. But I guess that in the end, Levertov in this book has a faith in language and expression itself to revise vision, to revise life. It’s a principle evident in poetry, inherent in the purpose and creation of this book, but also perhaps in the character of the activist. Many of these poems are recollected, taken from earlier publications and republished in this unique configuration. Defending herself against the charge of being narcissistic for “quoting herself,” Levertov writes,

Though the artist as craftsman is engaged in making discrete and autonomous works… yet at the same time, more unconsciously, as these attempts accumulate over the years, the artist as explorer in language of the experiences of his or her life is, willy-nilly, weaving a fabric, building a whole in which each discrete work is a part that functions in some way in relation to all the others. It happens at times that the poet becomes aware of the relationships that exist between poem and poem… It may be years later; and then, to get the design clear — ‘for himself and thereby for others,’ Ibsen put it — he must in honesty pick up that thread, bring the cross-reference into its rightful place in the inscape.

She plucked these poems from their original contexts and arranged them here, among letters and journal entries and other poems, because a kind of sense was emerging over time. She was seeing a more complete picture. Her “explorations in language” had captured pieces of a puzzle here put more fully together.

It gives me an important insight into the activist’s mindset, with its belief that our perspective is growing, is improving. Levertov’s hope in this book is to preserve the humane through this vehicle of poetry, to “stay alive” as a human being, in the face of the staggerlingly inhumane debacle of war. She uses language to capture her sense of a human race in a state of continual revision. There’s hope in that. Perhaps. Fallen world notwithstanding, wrestling match between knowledge and wisdom notwithstanding, battle between sinful nature and being made in the image of God notwithstanding.