Job Journal V: Toward some answers

It wouldn’t be fair to blog about my raw reading responses, then not come back and revise my initial impressions as I learn more about the book. This’ll probably be my last entry on Job for awhile, though there’s plenty I haven’t touched yet (Elihu, for instance). Here are some discoveries so far, followed by my reading list:

1.) I asked if the story sanctioned questioning, or discouraged it. Despite the tone of God’s answer in the story, the fact that Job gets an answer at all suggests that God honors the seeking heart. His respect for his creation extends to Job. What’s more, he speaks as to an equal: “Gird yourself up, and I will question you!” He is as honest with Job as Job is with him, allowing his anger to be apparent — but not to annihilate Job.

2.) Related to this was my complaint that Job’s prayer isn’t answered – that God used a kind of misdirection or non sequitur. I see a parallel between the way God answers Job without addressing his specific question of “Why?” and Jesus’ method of being asked one question, and answering another — puzzling to us, but not to those interacting with him. Here, Job’s question has been viewed as a legal complaint against God for his treatment. God’s answer is to justify himself by saying, basically, “My dealings with you are interwoven with the rest of what I’ve made. See how large and complex it is? See how many other questions are tied in with yours? Do you really want me to try to explain my creative process to you?” Job replies, “No. I see that it’s too big for me.” God’s answer isn’t evasive so much as impossible to reduce to Job’s terms.

Edited to add: Lewis’s chapter on divine omnipotence in The Problem of Pain is relevant here too: “With every advance in our thought the unity of the creative act, and the impossibility of tinkering with the creation as though this or that element of it could have been removed, will become more apparent. Perhaps this is not the ‘best of all possible’ universes, but the only possible one.” A creation spawned from a single, unified creative act means God can’t respond to Job’s question separately from a discussion of the rest of creation.

3.) I pointed out the wisdom of Job’s friends. Yup, they have some rudimentary wisdom, but its purpose in the story is to reveal its utter failure to account for what’s happening to Job. We know from the opening scene that this is a test, permitted by God, and their explanations nowhere acknowledge this as a possibility. Their conception of God allows him no room for free and independent action. This is what displeases God, and why Job’s point of view is superior to theirs.

4.) I suggested that Job matures. Maybe so, a bit. But this isn’t a bildungsroman. I think my overall sense that his righteousness is never in question tips the scales toward viewing him mostly as a static character. He gets a bit more daring, perhaps, but doesn’t substantially change. This is consistent with the type of literature this is: I’ve seen it referred to as myth, legend, parable, and wisdom literature, all of which lean toward the symbolic. As we know right away when we find ourselves witnessing a scene in Heaven, it’s not a record of actual events (except perhaps at a core that’s been varnished with many layers of fictional embellishment and poetry).

5.) I complained that the God of Job isn’t consistent with the covenant God of the rest of scripture. Well, no; its writing was probably pre-Mosaic, and Job’s cultural background wasn’t Hebraic. The book’s purpose seems to be as a “What if?” story… “What if we strip away the trappings of culture and reduce this conflict to the bare, primal bones: man, creator, evil.” Though there’s no “covenant” applicable to this relationship between God and Job, it’s still clear that this is a relational God; he enters into dialogue with Job.

6.) I questioned whether unconditional love for God is possible. Sad to say, I’m seeing that this is basically Satan’s question in the story. Perhaps “unconditional” isn’t the best word, but he (and the story as a whole) asks, “Is there a love for God that survives suffering, loss of his blessings, and deprivation of his justice?” Is God worthy of love if he doesn’t meet the conditions of our rational framework of justice? The answer of the story is yes. I think it’s what keeps Job petitioning God until the answer comes, and it’s what pleases God in the end.

Here are some resources (in no particular order) I’m exploring, and finding helpful, as I experience this book:

- Bill McKibben’s The Comforting Whirlwind: God, Job and the Scale of Creation offers the vision of creation God proudly sets forth from the whirlwind as a still-relevant paradigm.

- Stephen Mitchell’s translation of Job was Bill McKibben’s chosen text, and I’ve ordered a copy of my own. Though Mitchell’s decisions about what to include and what not to include are controversial (he leaves out Elihu’s speech entirely), the power of the language is a delight.

- Putting God on Trial is an online commentary by Robert Sutherland that offers philosophical, literary and legal analysis of Job.

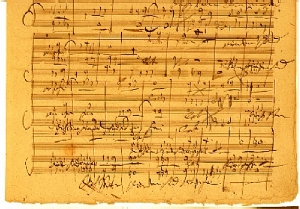

- William Blake’s Book of Job contains his own provocative illustrations. Without endorsing his theology, I think his pictures reflect some real insight.

- Jerry Gladson’s “Job,” in A Complete Literary Guide to the Bible, provides a run-down of the literary techniques and structural issues of Job.

- G.K. Chesterton’s Introduction to the Book of Job gives a theological overview.

- Beyond Suffering: Discovering the Message of Job by Layton Talbert is recommended by Barbara of Stray Thoughts. I look forward to getting ahold of a copy.

- David Malik’s Introduction to the Book of Job supplies an overview including information about authorship, genre, and historical context.