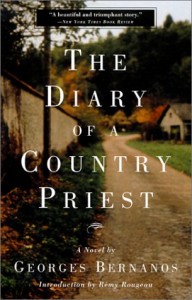

Diary of a Country Priest

I discovered Georges Bernanos’ The Diary of a Country Priest in the 1930’s list for the Decades Challenge. The library didn’t have a copy, so I ordered one; before it arrived, I read a different book for the 1930’s. So I was left with this one to read for pleasure, and because I’d paid for it. I don’t regret it.

I discovered Georges Bernanos’ The Diary of a Country Priest in the 1930’s list for the Decades Challenge. The library didn’t have a copy, so I ordered one; before it arrived, I read a different book for the 1930’s. So I was left with this one to read for pleasure, and because I’d paid for it. I don’t regret it.

It’s a bildungsroman, a novel carried not by action but by character development. We get to know the narrator, a young priest in a small country parish in France, through his diary. We have to trust him as he recounts conversations, personal reflections and struggles, and, increasingly, physical agony from the cancerous stomach tumor that kills him. I’m not Catholic, but I found this to be a challenging spiritual voyage that moved me beyond the familiar terrain of evangelical categories.

Two themes I found most compelling, both of which dealt with struggles in a life of faith. One was the tension between the difficulty of prayer, and the writing of the diary. The narrator speaks honestly of his failure to feel like he’s connecting with God in prayer many times throughout the novel. “Never have I made such efforts to pray,” he writes early on, “at first calmly and steadily, then with a kind of savage, concentrated violence… Yet — nothing.” The struggle of the act of praying never goes away, but the sense of companionship with God that the young priest longs for comes as he immerses himself in serving his parishioners. “I pray badly and not enough,” he laments. “Almost every day after mass I have to interrupt my act of thanksgiving to see some parishioners.” After one exhausting yet effective spiritual confrontation with one of his parishioners, he writes,

While I struggled with all my might against doubt and terror, a spirit of prayer came back into my heart. Let me put it quite clearly: from the very start of this strange interview I never once had ceased to ‘pray’ in the sense which shallow Christians give to the word. A wretched creature into which air is being pumped may look exactly as though it were breathing. That is nothing. Then air suddenly whistles through the lungs, inflates each separate delicate tissue already shrivelled, the arteries throb to the first violent influx of new blood — the whole being is like a ship creaking under swollen sails.

Prayer, then, is achieved – though not what he describes elsewhere as the “chatter, the dialogue of a madman with his shadow, or even less — a vain and superstitious sort of petition to be given the good things of this world.” Rather, this is prayer as a communion with God, a source of peace in suffering.

The narrator’s relationship with his diary forms an interesting counterpoint. Whereas the struggle to achieve a dialogue with God through verbal exchange never eases, the diary becomes a place to receive all the burden of utterance. The more he becomes reconciled to his diary, the more open he becomes to the “spirit of prayer” just described. Early on, he’s not so sure the experiment of keeping a diary is a good idea: “I hoped that this diary might help me to concentrate my thoughts… I had thought it might become a kind of communion between God and myself, an extension of prayer, a way of easing the difficulties of verbal expression.” But he feels guilty that it’s so emotionally satisfying, speaking of a false self that emerges as an audience and offers him pity and solace. By the end of the novel, however, he develops a great attachment to it. “More than ever I need this diary. It is only during these snatched moments that I am aware of some effort to see clearly into myself,” he writes. “If I keep to it strictly, morning and evening, my diary breaks up this wilderness, and sometimes I slip the last few pages into my pocket, to read them again on my long dull tramps from one end of the parish to another.” By the end of the story, when he leaves the parish for what turns out to be the last time, he can’t bear to leave it behind. Far from becoming an idol, it seems to relieve prayer of the craving for self-knowledge, and leaves it instead for the purposes of spiritual nourishment.

Against this backdrop of the working out of a relationship between writing and prayer is the novel’s main concern: suffering. The young cleric isn’t particularly popular among his parishioners, but it seems to be because he’s spiritually genuine and makes people uncomfortable. Unlike several of his contemporaries, he has no use for the church’s compromise with social status or political order. He never fails to read others’ suffering, and to share it. It’s not long before we realize he’s a Christ figure, right down to subsisting on a diet of only bread and wine. He’s magnetic, attracting even those who seem to want to avoid him. I really liked these passages; they stretched me. His insight into other characters is penetrating, and he never seems to follow a set of predetermined rules in his interactions. Instead he’s actuated by compassion, and I found his insights fascinating and appealing. For instance, recounting a dialogue with a jaded old doctor, he writes,

I know I have very little experience, yet I seemed instantly to recognize a certain inflection betraying some profound spiritual hurt. Others perhaps might then be able to find the right words to appease and persuade. I don’t know such words. True pain coming out of a man belongs primarily to God, it seems to me. I try and take it humbly to my heart, just as it is. I endeavor to make it mine — to love it.

Later, speaking with a deeply angry and grieving woman, he states, “A priest pays attention only to suffering, provided that suffering is real… I’m not a professor of moral theology.” Rather than functioning as an answer man, he sees himself as a companion in suffering. Toward the end of the book he remarks, “I believe that ever since his fall, man’s condition is such that neither around him nor within him can he perceive anything, except in the form of agony.”

It’s not for the meek and fainthearted, is it? Maybe that’s what I like best about the book. While I don’t feel I’ve fully grasped it all, it represents an honest struggle with hard questions. In a curious coincidence, I switched on the radio as I was making supper tonight, thinking about this book. Terry Gross was just completing this interview with Bart Ellman, author of the book God’s Problem. A professor of religion, Ellman is a former Christian turned agnostic by the problem of suffering in the world. He’s clearly someone immersed in the objective fallacy, for he spoke with thinly concealed pride of having taught religion for many years without ever having a conversation with a colleague in the department about his personal beliefs. What a different approach to the questions of faith! For myself, I prefer to listen to those who’ve wrestled with these questions at a deeper level than just the intellect, plunging themselves into the darkest aspects of human existence with profound empathy and compassion — like this young narrator, Mother Theresa, the Old Testament prophets, or Christ himself.